PWD Response to “Unraveling the Facts”

The American Littoral Society is a valued partner of the Philadelphia Water Department, and we appreciate their continued passion for achieving water quality improvements to our region’s waterways. However, a recent publication led by the American Littoral Society and supported by additional contributors titled “Unraveling the Facts” includes positions and assertions related to PWD’s programs that we feel warrant clarification and/or correction.

“Unraveling the Facts” presents as an FAQ-style document; however, the contents of the document feature a mix of opinions, interpretations, and direct quotes from PWD sources bereft of context, leading to potential for misunderstanding on the part of the reader. The “Unraveling the Facts” document has been distributed to undisclosed recipients, and PWD has received questions and requests for information resulting from the misunderstanding of content as presented.

PWD has been proactive for decades in data sharing, development of cutting-edge tools for data analysis, simulations, monitoring, engineering analyses and environmental ethics. We welcome review and comment by partners and will continue to do so. We encourage our partners to review materials posted on our website for themselves rather than relying on the interpretations of this information by others, as valuable data and context are often lost in that process.

The two principal areas of focus for Unraveling the Facts are:

- Perceived limitations to the availability of impervious cover in Philadelphia to meet program goals; and

- Perceived implications of climate change on PWD’s Green City, Clean Waters combined sewer overflow initiative and its implementation progress.

PWD offers the following summaries to respond to these areas of focus. Additionally, included below is a subset of questions from the Unraveling the Facts document to offer additional information and context to the information provided in the document.

Perceived limitations to the availability of impervious cover in Philadelphia to meet program goals:

The Philadelphia Water Department staff have spent the past 13 years implementing an innovative approach to water resources management and investments in our communities. Our team has taken a vision called Green City, Clean Waters and ushered it from idea to reality, by creating the programs, policies, and tools necessary to facilitate this award-winning program. This vision has been widely copied around the world. We have faced challenges and obstacles head on, while continuing to make adjustments when needed, and will continue to do so in the coming years.

However, piloting a cutting-edge approach does not come without challenges. Over the past decade, there have been a number of lessons learned, including project collaboration assumptions not realized, geographic areas and land use types that proved more challenging for implementation, and costs often higher than projected. The implementation approach has been focused on prioritizing projects based on feasibility and cost-effectiveness, while ensuring regulatory compliance and distribution of projects across the combined sewer system.

PWD’s approach includes system-wide implementation as the program endpoint is 85% equivalent mass capture on a combined sewer system-wide average annual basis. Accomplishing this scale of implementation necessitates working in every neighborhood and building infrastructure systems wherever they are physically feasible and reasonably cost effective. Over the course of the first decade of implementation we have evaluated the physical constraints present in almost every neighborhood (narrow streets, utility conflicts, steep slopes, mature trees, bedrock, flooding, trash, vacant lots, etc.). Some of these constraints would present challenges regardless of whether green or grey infrastructure were being implemented.

In the most recent Evaluation and Adaptation plan (EAP) produced at Year 10 (2022), PWD highlighted a number of challenges being tracked in the years ahead. These include the potential for increased capital and operating costs for GSI implementation as the annual expected delivery of GSI projects increases. This is partially because GSI implementation opportunities are becoming more constrained as siting opportunities become more limited and complex.

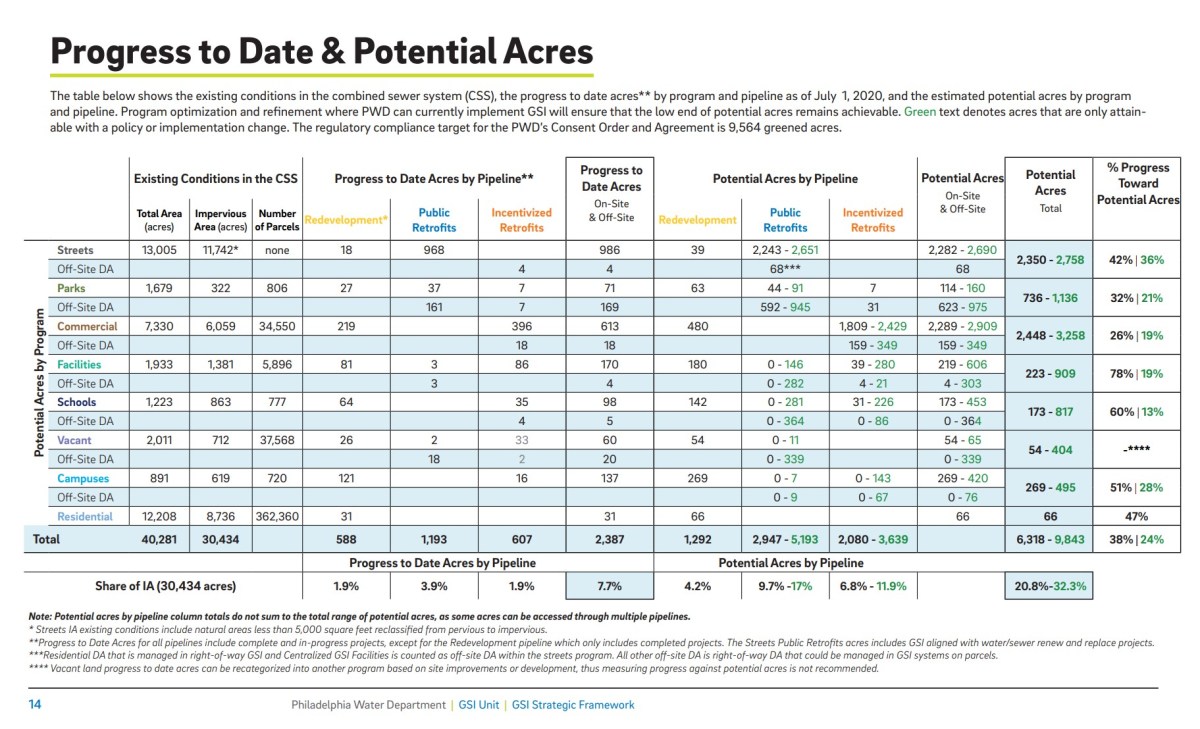

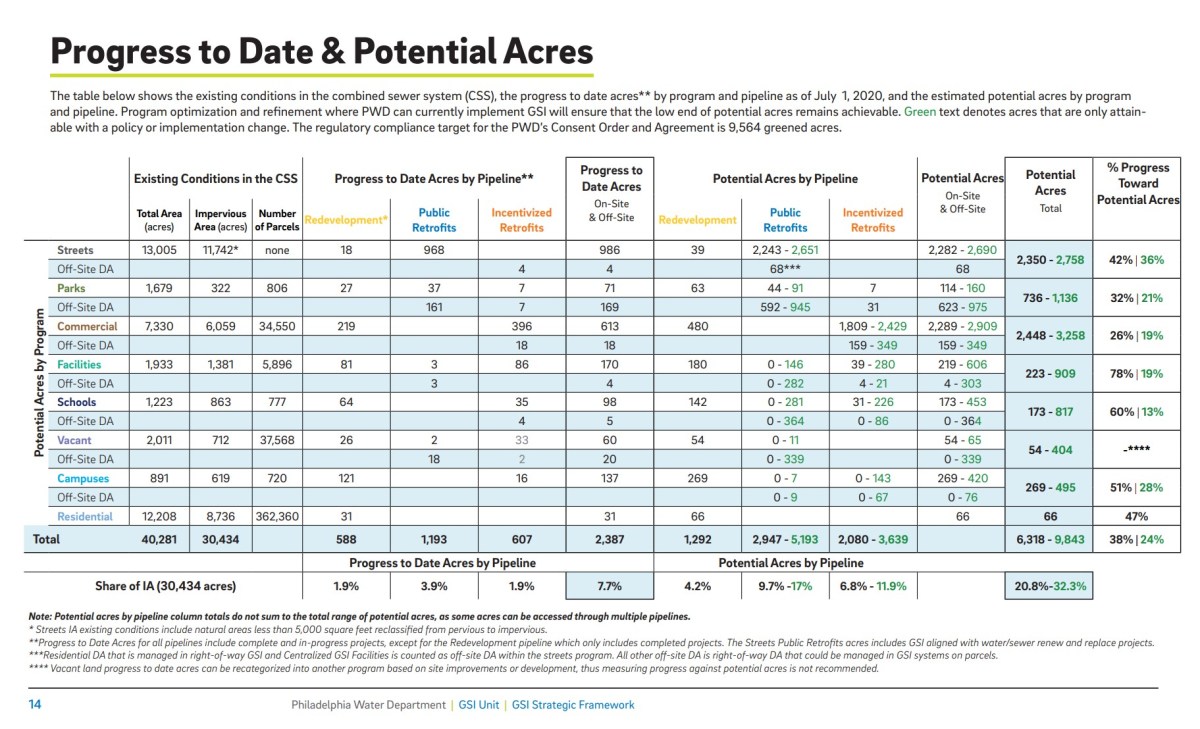

PWD has posted on its website a GSI Strategic Framework since April of 2022, which summarizes detailed analyses performed to determine the available “greenable” space within the City. Results indicate that there is ample greenable space available to meet program targets. The report also highlights policy recommendations to facilitate the achievement of targets.

While PWD anticipated from the inception of this program both a challenging and dynamic environment, the forthcoming magnitude of compounding obligations unrelated to combined sewer overflows was not foreseen. In the coming years, PWD may be required to replace lead service lines, remove emerging contaminants like PFAS from our drinking water, increase resiliency at our water treatment and water pollution control plants, implement advanced pollutant removal technologies at our wastewater treatment plants, while also mitigating risks associated with aging infrastructure, the impacts of climate change on human health and our ecosystems, and potential additional regulatory obligations. Water resources management is a complex and iterative process, and PWD designed a program to accommodate that reality. Adaptive management is a core tenet of PWD’s approach to utility management and was formally incorporated within the GCCW program as a tool to support potential program changes as needed. The GCCW approach was designed and envisioned to be incremental and flexible with the incorporation of adaptation tools and processes as a principle, not an afterthought.

Perceived implications of climate change on GCCW Implementation Progress:

Impacts from climate change pose a significant challenge to water utilities across the nation. PWD created the Climate Change Adaptation Program (CCAP) to keep abreast of ongoing advances in climate science, and to understand the impacts that climate change will have on all PWD core services, which include drinking water, wastewater and stormwater systems.

It is now almost universally acknowledged that human-caused greenhouse gas emissions are causing our climate to change much more rapidly than any natural cycle has caused in the past. In Philadelphia, this generally means temperatures are rising, rainfall is changing and water levels in tidal and non-tidal rivers and creeks are rising.

Because of natural variability, however, climate scientists generally agree that at least 30 years of continuous data are needed to get a reasonably accurate picture of current rainfall patterns. Naturally variable precipitation patterns have been a known challenge for urban stormwater management for centuries, and now climate change impacts are (and will continue) pushing the wide range of possible rainfall amounts upward by some uncertain amount.

Recent years have been particularly wet, and this could very well be a result of climate change. Each stormwater system or combined sewer system will respond differently to the frequency and intensity of the storms that occur each year. Rainfall in Philadelphia is characterized by a large amount of natural variability. Annual total rainfall can be over 60 inches in some years, and as low as 30 inches in others. Every year the frequency and volume of CSOs changes, depending on the amount of rainfall in that year. This is normal and expected, and PWD reports its annual CSO discharges in its annual reports. It is for this reason that regulatory targets must depend on a more fixed target.

Making changes to programmatic targets and assumptions using only the past few years of observed data is unwise. These impactful decisions have consequences for the operations, management, and financial feasibility of PWD infrastructure systems and must be made with a sufficient period of record of observed data while considering future climate change projections where possible. To address the risk of climate change impacts on PWD services, PWD is already utilizing climate change projections to inform the planning and design of infrastructure that will have a useful service life (need to remain reliably operational) through the end of century or beyond.

PWD is committed to considering climate change for new infrastructure that is being planned and designed to meet existing regulatory requirements. In 2022, PWD instituted Department-wide policy requiring the use of the Climate-Resilient Planning & Design Guidance, in the planning and design of all PWD projects to the extent feasible. This includes projects that are planned, designed and implemented as part of our CSO program. Our Guidance has already informed several major infrastructure projects and our CCAP team continues to work with internal staff and project teams to mainstream the use of climate science and projections. As an example, we are using sea level rise projections from the Guidance to inform quantitative, cost-based coastal flood risk assessments at all three of our Water Pollution Control Plants (WPCPs) on the tidal Delaware River. The risk assessment results will directly inform the development of flood mitigation strategies at our WPCPs, protecting them from the impacts of future sea level rise and storm surge. Implementing this Guidance Department-wide helps to ensure that our infrastructure remains operationally and economically viable, and that PWD can continue to achieve its level of service goals, despite the impacts of climate change. One of the advantages of a CSO program that is incrementally implemented and includes distributed infrastructure (i.e. numerous, smaller-scale projects rather than a few very large projects), is the ability to adapt design criteria and/or implementation tools as more recent climate information becomes available.

Per PWD policy, the Climate Resilient Planning and Design Guidance has been used to inform the Green City, Clean Waters program, including the siting and/or design of green and traditional infrastructure, as well as evaluation of drainage system/collection system risks under climate change. Both traditional gray infrastructure and Green Stormwater Infrastructure have their advantages and disadvantages, and both, when thoughtfully designed and implemented, can account for climate and other related risks, and will serve the purpose of controlling the impacts to the receiving water bodies. Implementation of the GCCW program is evaluated through the lens of climate change as we determine appropriate tools and potential adaptations and enhancements.

Subset of Questions Featured in “Unraveling the Facts” that would benefit from additional context and information:

The following questions were presented in the Unraveling the Facts document, with answers that were partial and/or misinterpretations of PWD positions, materials or history. We feel that readers of that document would benefit from additional information and context as many of the answers as presented will cause confusion.

1. Brief History of Green City, Clean Waters (GCCW)

“Unraveling the Facts” outlines a brief summary of the history of the Green City, Clean Waters program, however several of the programmatic elements are presented incorrectly or out of order. The origin of the program known as Green City, Clean Waters is as follows:

- PWD’s initial Long-term CSO Control Plan (LTCP) was developed in 1997.

- In 2005, PWD committed to development of an updated LTCP with a plan to meet water quality standards.

- PWD’s Long-term CSO Control Plan Update (LTCPU) was developed and submitted in 2009 and was given the public facing name “Green City, Clean Waters”.

- Regulatory review and negotiations related to the 2009 LTCPU submittal were concluded in 2011 with the signing of the Consent Order & Agreement (COA) with the PADEP.

- The COA codified this presumption-based plan with an 85% equivalent mass capture endpoint and a Water Quality Based Effluent Limit (WQBEL) with Performance Standards to be met at 5-year intervals.

- Shortly thereafter, the USEPA formalized their approval of the plan with the 2012 Administrative Order for Compliance on Consent (AOCC).

Note: The Green City, Clean Waters plan is a CSO mitigation strategy and does not have targets, performance standards or permit related obligations for the MS4 portion of the City.

2. What are some of the key provisions of the Green City, Clean Waters plan?

The content provided in the “Unraveling the Facts” document does not answer this question. Management of impervious cover from 34% of the combined sewered portion of the City is an implementation strategy, not a “Key Provision” of the plan.

The “key provision” of the plan is that the City will construct and place into operation the controls described as the selected alternative in the amended LTCPU to achieve the elimination of the mass of the pollutants that otherwise would be removed by the capture of 85% by volume of the combined sewage collected in the Combined Sewer System (CSS) during precipitation events measured on an agreed upon, system-wide annual average basis.

Additional provisions are outlined in the form of a Water Quality Based Effluent Limit (WQBEL):

| Metric | Units | Base line value | Cumulative amount as of Year 5 (2016) | Cumulative amount as of Year 10 (2021) | Cumulative amount as of Year 15 (2026) | Cumulative amount as of Year 20 (2031) | Cumulative amount as of Year 25 (2036) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE / SW / SE WPCP upgrade: Design | percent complete | 0 | TBD June 2013 | TBD June 2013 | TBD June 2013 | 100% | 100% |

| NE / SW / SE WPCP upgrade: Construction | percent complete | 0 | TBD June 2013 | TBD June 2013 | TBD June 2013 | 100% | 100% |

| Miles of interceptor lined | Miles | 0 | 2 | 6 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 |

| Overflow Reduction Volume | million gallons per year | 0 | 600 | 2,044 | 3,619 | 5,985 | 7,960 |

| Equivalent Mass Capture (TSS) | Percent | 62% | Report value | Report value | Report value | Report value | 85% |

| Equivalent Mass Capture (BOD) | Percent | 62% | Report value | Report value | Report value | Report value | 85% |

| Equivalent Mass Capture (Fecal Coliform) | Percent | 62% | Report value | Report value | Report value | Report value | 85% |

| Total Greened Acres | Greened Acres | 0 | 744 | 2,148 | 3,812 | 6,424 | 9,564 |

3. What are the challenges facing PWD in implementing its Green Acres targets?

Unraveling the Facts puts a great deal of emphasis on the position that there is not enough “greenable” space within the City to meet the program requirements. Within this portion of the Q&A, the document references University of MD Environmental Finance Center and The Nature Conservancy’s, “Sustainable Funding for Philadelphia’s GCCW Plan” as the source of data and analyses to make this point. The Sustainable Funding for Philadelphia’s GCCW Plan focuses on the need for expansion of implementation approaches on private land.

Posted on our website is the 2022 GSI Strategic Framework, which summarizes detailed analyses performed to determine the available “greenable” space within the City. Results indicate that there is ample space available to meet program targets, however there are critical policy recommendations to facilitate implementation on much of that land. The challenges that PWD faces are related to feasibility and costs of implementing on constrained spaces within dense urban conditions of the City.

4. What area is covered by the GCCW plan?

The answer provided in “Unraveling the Facts” features the receiving waters, with most emphasis on the portion of the Delaware River alongside the City of Philadelphia.

What it does not describe is the 64 square mile portion of the City covered by the Combined Sewer System where implementation of this program is focused. Approximately 60 percent of the City of Philadelphia is served by a combined sewer system, which transports both runoff from storms and wastewater from homes and buildings. The City has 164 permitted Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) outfalls along the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers and the Cobbs, Tookany/Tacony-Frankford, and lower Pennypack creeks. View a map of the City’s sewersheds.

Green City, Clean Waters uses a combination of green infrastructure and traditional infrastructure solutions to reduce combined sewer overflow volumes. The Green City, Clean Waters program has reduced over three billion gallons from baseline during the first 12 years of program implementation.

5. How does GCCW Plan incorporate equity?

The response provided in “Unraveling the Facts” infers that the PWD program and approach do not have explicit equity commitments and obligations, and this is untrue.

As a department, PWD maintains level-of-service goals to ensure equitable investments throughout the system. Additionally, PWD’s system-wide implementation approach for the GCCW program was the product of our intent for an equitable distribution of investments across the City. As described in Consent Order & Agreement Supplemental Document #5, Rationale for Equal Distribution of Green Stormwater Implementation in all neighborhoods, the proposed Combined Sewer system-wide distribution of green stormwater infrastructure is intended to yield water quality benefits and improvements across the City’s waterways, ensuring equal access for all to the expected environmental, social and economic benefits derived from green infrastructure.

PWD is committed to maximizing the benefits of infrastructure investments. PWD will continue to conduct planning analyses and prioritize GSI projects in areas where the most volume reduction per impervious area is possible as well as in areas to support other city and community initiatives. The department is also moving toward a more integrated approach for water, sewer, and GSI project implementation which aims to streamline construction disturbance and provide comprehensive updates to neighborhoods. Consequence of failure is a key indicator of prioritization of infrastructure updates and the department will continue to map and set specific equity driven goals in alignment with City efforts. The federal Justice 40 initiative can be used as a model and will help continue to drive investment in under-resourced neighborhoods; aiming for over 40 percent of federal funding to go to census tracts identified as disadvantaged communities, underserved, and overburdened by pollution. A large percentage of the city is categorized as disadvantaged in several tools: Climate and Economic Justice Screener Tool, EPA EJScreen, PA DEP Environmental Justice Areas Viewer, and DVRPC’s Indicators of Potential Disadvantage. PWD will continue to invest in these disadvantaged neighborhoods. Investments made on water, sewer, and GSI infrastructure anywhere in the city, even outside of Environmental Justice (EJ) areas, provide benefits to the larger community through improvement of water quality and service.

PWD’s direct investments in EJ communities, and investments that advance water quality of streams and rivers benefit all communities within the service area and beyond. When possible and appropriate, tailoring GSI investments to maximize tree and vegetation installation can provide additional benefits to EJ communities.

6. Why are there concerns with the original targets?

Unraveling the Facts suggests that the “problem” is that the typical year was based on rainfall data from 2006. This highlights a fundamental misunderstanding of how a typical year is developed, how much data is analyses to develop this, and how it is then used to describe implementation progress over time.

The “typical year” concept was proposed by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) in the CSO Control Policy (1994) as a means of accounting for performance in terms of system-wide average annual hydrologic conditions, recognizing the variability of year-to-year rainfall conditions. The identification of an average annual precipitation record, therefore, is critical for the evaluation of combined stormwater system (CSS) performance as well as to establish a firm benchmark for measuring progress towards meeting our regulatory obligations.

The rainfall conditions over the Philadelphia CSS area were characterized using a long-term historic hourly rainfall record over a 59-year period (1948-2006), from the National Weather Service Cooperative Station located at the Philadelphia International Airport (PIA) (WBAN#13739). Statistical analyses of the long-term record are performed to determine the average frequency, volume, and peak intensity of rainfall events. Identification of long-term average hydrologic conditions over the CSS is based primarily upon average annual and monthly precipitation volumes determined from the long-term record. Comparisons are made between the individual annual precipitation volumes and the long-term average to identify relatively ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ years. By this measure, 1983 and 1922 are the wettest and driest years on record, respectively. Furthermore, it is seen that during this period (since 1990) one year, 1996, is characterized as being wet and five individual years are characterized as being dry by having a total annual precipitation volume greater than one standard deviation from the mean.

Developing a regulatory target such as a typical year is complex. As described in LTCPU Section 5 (p. 21), “the identification of long-term average hydrologic conditions is often based primarily upon average annual and monthly precipitation volumes determined from the long-term precipitation record. Comparisons are made between the annual precipitation volumes and the long-term average to identify relatively ‘wet’ and ‘dry’ years. CSO occurrence, however, is a complex function of storm event characteristics such as total volume, duration, peak intensity and length of antecedent dry period or inter-event time. In addition to annual precipitation volumes, event-based analysis of the long-term precipitation record is used to identify short-term periods that best represent average annual CSO frequency and volume statistics for evaluation of collection system performance. In order to identify continuous periods likely to generate CSO statistics representative of the long-term record, continuous 12-month periods selected from the recent PWD data from it 24 rain gages from 1990-2006 were evaluated against the period of record based on the total annual precipitation volume, the annual number of precipitation events and the distribution frequency of event peak hourly precipitation intensity. Details of the event-based analysis and procedure may be found in the Supplemental Documentation Volume 5: Precipitation Analysis.”

The baseline condition from which GCCW progress is measured was established based on combined sewer collection system and treatment plant conditions as they existed in 2006, prior to GCCW implementation. Using a typical hydrologic year (developed as described above), provides us with average annual conditions for establishing CSO baseline metrics as well as implementation metrics that enable us to evaluate and report on progress to the regulatory agencies.

The baseline condition was developed as a range of combined sewer overflow volumes (CSO) from 10.3 billion gallons to 15.9 billion gallons. The average value of 13.1 billion gallons has been the established point from which the 7.96 billion gallons CSO volume reduction will be measured. Rainfall variability can be large between years which impacts the year-to-year CSO volume directly; this has been acknowledged by regulatory agencies and the scientific and engineering community.

7. Is the City meeting its targets in the GCCW plan?

The Unraveling the Facts document relegates progress made to date as “paper compliance” because the progress is measured using a typical year rather than annual variability.

As previously described, in order for PWD to develop an LTCP that is implementable and measurable over the plan duration, the CSO-related targets must be fixed and unambiguous. Annual conditions are neither fixed nor unambiguous and would not produce consistent annual conditions to enable progress tracking or comparison over time.

PWD has met or exceeded all WQBEL performance standards at years 5 and 10.

Table 2- 1: Up-to-Date WQBEL Values

| Metric | Units | Base Line Value | Year 10 WQBEL Target | Cumulative amount as of Year 10 (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NE WPCP Improvements | Percent Complete | 0 | See Section 2.2.1 | |

| SE WPCP Improvements | Percent Complete | 0 | See Section 2.2.2 | |

| SW WPCP Improvements | Percent Complete | 0 | See Section 2.2.3 | |

| Miles of Interceptor Lined | Miles | 0 | 6 | 9.2 |

| Overflow Reduction Volume | Million Gallons Per Year | 0 | 2,044 | 3,080 |

| Equivalent Mass Capture (TSS) | Percent | 62% | Report value | 77.5% |

| Equivalent Mass Capture (BODs) | Percent | 62% | Report value | ~100.0%* |

| Equevalent Mass Capture (Fecal Coliform) | Percent | 62% | Report Value | 77.1% |

| Total Greened Acres | Greened Acres | 0 | 2,148 | 2,196 |

8. Can the City continue to meet its existing greened acre targets in the GCCW plan?

Unraveling the Facts infers that there is not enough public land to meet the target – again referencing the UMD report. PWD does not disagree with the challenges of constraints and increasing costs for implementation, however we take issue with the notion that availability of impervious cover to manage is the greatest challenge. Both the UMD report and the GSI Strategic Framework highlight land available for implementation, with policy limitations as the greatest challenge. Both the Year 10 EAP and the GSI Strategic Framework should be reviewed for a more comprehensive picture of the challenges and opportunities for implementation of GSI throughout the system.

9. Why is there a common misunderstanding of the GCCW targets?

While the Unraveling the Facts document is seemingly attempting to clarify misunderstandings, their response to this question may add more confusion than clarity. The GCCW program targets are clearly defined in the Consent Order & Agreement through establishment of the WQBEL. The WQBEL includes both numeric performance standards and a schedule with interim targets.

PWD has a presumption-based program whereby we will construct and place into operation the controls described as the selected alternative in the amended LTCPU to achieve the elimination of the mass of the pollutants that otherwise would be removed by the capture of 85% by volume of the combined sewage collected in the Combined Sewer System (CSS) during precipitation events on a system-wide annual average basis. While there will be a remaining volume of overflow coming from the combined sewer system at the completion of the program (approximately 5 billion gallons during average annual conditions), the program meets the standards and requirements of the federal guidelines and presumes that at the conclusion of the program, water quality standards will be attained.

The GCCW program meets requirements of the CSO Control Policy, which states that: “A program that meets any of the criteria listed below would be presumed to provide an adequate level of control to meet the water quality-based requirements of the CWA, provided the permitting authority determines that such presumption is reasonable in light of the data and analysis conducted in the characterization, monitoring, and modeling of the system and the consideration of sensitive areas described above. These criteria are provided because data and modeling of wet weather events often do not give a clear picture of the level of CSO controls necessary to protect WQS.

- No more than an average of four overflow events per year…

- The elimination or the capture for treatment of no less than 85% by volume of the combined sewage collected in the CSS during precipitation events on a system-wide annual average basis…

- The elimination or removal of no less than the mass of pollutants, identified as causing water quality impairment…, for the volumes that would be eliminated or captured for treatment under paragraph ii… ” (Section II.C.4.a.)

Like every CSO program, at completion, monitoring is required to determine is WQ standards are being met.

10. How does PWD’s report of overflow “reductions” relate to the actual amount of stormwater captured?

We would caution against use of observed data from USGS gages or from the City’s annual Discharge Monitoring Reports (DMRs) being used to draw conclusions regarding program performance and progress. This is for the same reason the EPA notes in the LTCP guidance— due to significant variability in annual rainfall, this type of analysis would not be prudent in determining whether a program is effective, nor would this information be a clear indication of the extent to which climate change has altered regional precipitation patterns. In this region, we have wet years (such as we are seeing in this current year – which is also influenced by climate patterns such as El Nino) and dry years. The development of a typical year considers these extremes and seeks to determine long-term trends representative of climatic conditions at the time of CSO program development.

While we acknowledge that impacts of climate change are evident, the regulatorily defined typical year is not obsolete in the context of current compliance obligations. The regulatory typical year provides an unambiguous benchmark for establishing regulatory targets and evaluating the performance improvements and effectiveness of alternatives used to meet Clean Water Act requirements. The typical year is representative of the current, average climate in the region at the time of CSO program development. Establishing a baseline condition and understanding of typical year conditions at the time of LTCP development remains essential for evaluating progress as projects are incrementally executed throughout the program’s 25-year duration.

11. Does PWD have authority to adapt the GCCW plan?

Within our current COA, which includes above-stated targets, metrics and baseline conditions, PWD has the authority to adapt and is continuously doing so, as documented in our EAPs.

Adaptive management is one of the core principals of successful watershed improvement programs; dynamic conditions such as land development, changing/new regulations, and the implications of climate change, among others, necessitate an agile approach that incorporates adaptive management tools. PWD formalized incorporation of adaptive management principles in the Green City, Clean Waters program and has been adapting and enhancing the implementation approach since the program started. There have been tweaks and enhancements to the implementation approach throughout the first 12 years of the program, as documented in both the Years 5 and 10 Evaluation and Adaptation plans (EAP). While the EAPs have featured adaptations to date that have been focused on optimizing the current toolbox (e.g. design enhancements for GSI projects, collection system modifications to optimize flow to the plants, etc.) this is not reflective of all of the potential adaptations to the program that PWD has evaluated. PWD has been and will continue to work tirelessly to determine the most effective, cost-efficient implementation pathways to achieve waterway improvements, using both green and traditional infrastructure.

Data collection and analysis is paramount within this multi-decade program as conditions have evolved and continue to evolve. We recognize the importance of continuously assessing and adjusting inputs as we gather an understanding of performance, costs and implications of other related and unrelated investments. PWD has been initiating internal working groups as needed to assess risks and/or opportunities as they emerge.

Adaptation of the program itself, including the WQBEL, baseline conditions, and negotiated plan elements, would require negotiations with our regulators, PADEP and EPA, and necessitate a modification to or replacement of the COA.

12. What does the PWD’s own Climate-Resilient Guidance specifically recommend?

After describing the tools that PWD has developed to understand climate science, “Unraveling the Facts” states the following: “In short, PWD seems to already have the tools at hand to re-evaluate the GCCW outcomes in light of climate change, and so provide guidance for adaptive management of the GCCW plan starting now. However, public access to this material has been eliminated from the PWD guidance.”

There seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding on the scope and primary purpose of the tools developed by our Climate Change Adaptation Program. The guidance contains actionable science and tools that are used by PWD planners and design engineers to ensure the long-term resilience of infrastructure plans and projects this Guidance, which is a living document that will be updated as the science evolves, is available online. In contrast, the average annual condition/typical year is part of the legally binding COA, and any modification or evaluation of the typical year and program performance, respectively, must be done in consultation with PWD’s regulatory agencies. Updating the GCCW can only be done in agreement with the regulatory agencies.

PWD is not eliminating public access to information as there is no information related to GCCW to share at this time. As previously described, all new infrastructure is planned, designed and implemented based on climate guidance.

13. How does increased rainfall from Climate impact upcoming PWD permits?

PWD would like to highlight that historically, there has not been a direct link between the impacts of climate change and PWD’s permits. PWD’s permits do not reference a typical hydrologic year.

14. What is the potential impact on upcoming state and federal review of PWD NPDES permits?

“Unraveling the Facts” states that there is “the need for PWD to manage for current and expected impacts of climate change NOW, rather than waiting for evaluation following the end of the GCCW plan in 2036.”

The notion that PWD will not consider evaluation of climate impacts until completion of the program in 2036 could not be further from the truth. PWD has developed and instituted (since 2022) use of Climate Resilient Planning and Design Guidance for new projects. PWD recently completed an update to the guidance based on additional understanding of the evolving science, which will enhance our planning for these conditions. (The updated Guidance, Version 1.1, will be posted online in the near future). PWD also employs the use of climate change projections in infrastructure, facility and system-based risk assessments. Before action is taken to significantly modify or change course on any program or long-term plan, a sufficient understanding of current and future conditions and risks is needed. Climate change risk assessments are and will continue to be used to inform long-term planning and regulatory compliance efforts at PWD.

15. How does increased rainfall due to climate change impact local communities?

PWD would like to note that Green City, Clean Waters is not a flood mitigation program, so while we recognize that implications of climate change include flooding, we want to be clear that the GCCW program is not intended to mitigate flood impacts throughout the City.

PWD disagrees with the statement that “the GCCW plan does not have any provisions for ensuring equity in how it sites GCCW projects, invests money and creates local benefits.” PWD’s direct investments in EJ communities, and investments that advance water quality of streams and rivers, benefit all communities within the service area and beyond. When possible and appropriate, tailoring GSI investments to maximize tree and vegetation installation can provide additional benefits to disadvantaged communities.

16. Why should action be taken to adapt or complement provisions of GCCW plan?

Points covered in Unraveling the Facts’ response include the following:

- “The GCCW program should be amended to account for climate change”. To this end, PWD has amended the approach to account for climate change by establishing the Climate-Resilient Planning & Design Guidance and committing to its use for projects considered for implementation.

- “PWD should take advantage of the “limited window” of available federal infrastructure funds”. To that end, PWD has been working with state and federal agencies to take full advantage of funding opportunities available to the City. The City has pursued hundreds of millions of dollars of state and federal funding to support implementation of numerous PWD programs.

17. Is PWD legally allowed to modify its GCCW Plan?

While PWD has the ability to make modifications to the implementation approach through the EAP, PWD does not have the ability to elect changes to negotiated elements of the Consent Order & Agreement.