2020 Drinking Water Quality Report

Published in 2021

Your tap is locally sourced.

Water from our rivers is treated to the highest standards.

Contact Information

Philadelphia Water Department

1101 Market St.

Philadelphia, PA 19107

Public Water System ID #PA1510001

Brian Rademaekers

Public Information Specialist II, Public Affairs

(215) 380-9327

Sharing this report

water.phila.gov/2020-quality

View as PDF

Please share this report with all people who drink this water, especially those who may not have received this notice directly (for example, people in apartments, nursing homes, schools and businesses). You can do this by posting this notice in a public place or distributing copies by hand and mail.

To receive a printed copy of this report, please email: waterquality@phila.gov

A message from the Commissioner

It is my pleasure to present our 2020 Water Quality Report, created to ensure Philadelphians know what the science shows: our drinking water is safe, clean, and top-quality.

During a year when the pandemic made it critically clear that having clean water at home is essential, we met many challenges and delivered on our daily pledge to protect the health and safety of those we serve.

This report features water quality information collected throughout 2020.

You will also find information about where your water comes from, and how we protect your safety as water moves from the rivers, through our plants and pipes, and into your home.

This new, more accessible approach — showing customers how we maintain quality at every step — was developed by our Public Affairs team in close collaboration with our Bureau of Laboratory Services.

Following water on its journey to your tap also shows that access to excellent quality water around the clock is made possible only through the hard work and dedication of more than 2,000 Water Department employees.

We hope you take the time to review the wealth of information in this report.

If you’d like to volunteer and help keep our waterways clean, please follow @PhillyH2O on social media, call our 24-hour hotline at (215) 685-6300, or visit water.phila.gov

You can also sign up for email and text alerts at phillyh2o.info/signup.

Sincerely,

Randy E. Hayman, Esq.

Water Commissioner

How this document is organized

This story follows our water quality work from source and treatment through delivery to your home.

Part One: Source & Treatment

Philly’s local water sources, and what we do to keep water safe

Part Two: Delivery

Safe transit through the system

Part Three: At Home

The final stretch to your tap

2020 Data Tables & more

Look for these quick guides throughout the report:

A Closer Look

Charts and graphs let you see the data in a new way ![]()

Here’s the story of why we do this test

Handwritten notes explain how and why we do these tests ![]()

☑ RESULT:

All results are better than the recommended federal levels.

Look here for key takeaways ![]()

Part One: Source & Treatment

We take water from the Delaware River at one of our three treatment plants in Philadelphia

Your water begins in freshwater streams

Philadelphia’s water comes from the Delaware River Watershed. The watershed begins in New York State and extends 330 miles south to the mouth of the Delaware Bay. The Schuylkill River is part of the Delaware River Watershed.

Protection starts at the sources.

We take a holistic approach, beginning with Philadelphia’s water supply characteristics. We monitor actual pollution sources, and look for potential sources of contamination. We keep track of water availability and flow.

Our wide range of tools includes:

Research

- We study regional influences like natural gas drilling, and global influences like sea level rise.

Projects in the field

- Protecting against stormwater and agricultural runoff.

- Monitoring water contaminants.

Partnerships

- We team up with upstream groups to help safe water flow to Philadelphia from areas outside the city.

Looking closely for potential threats

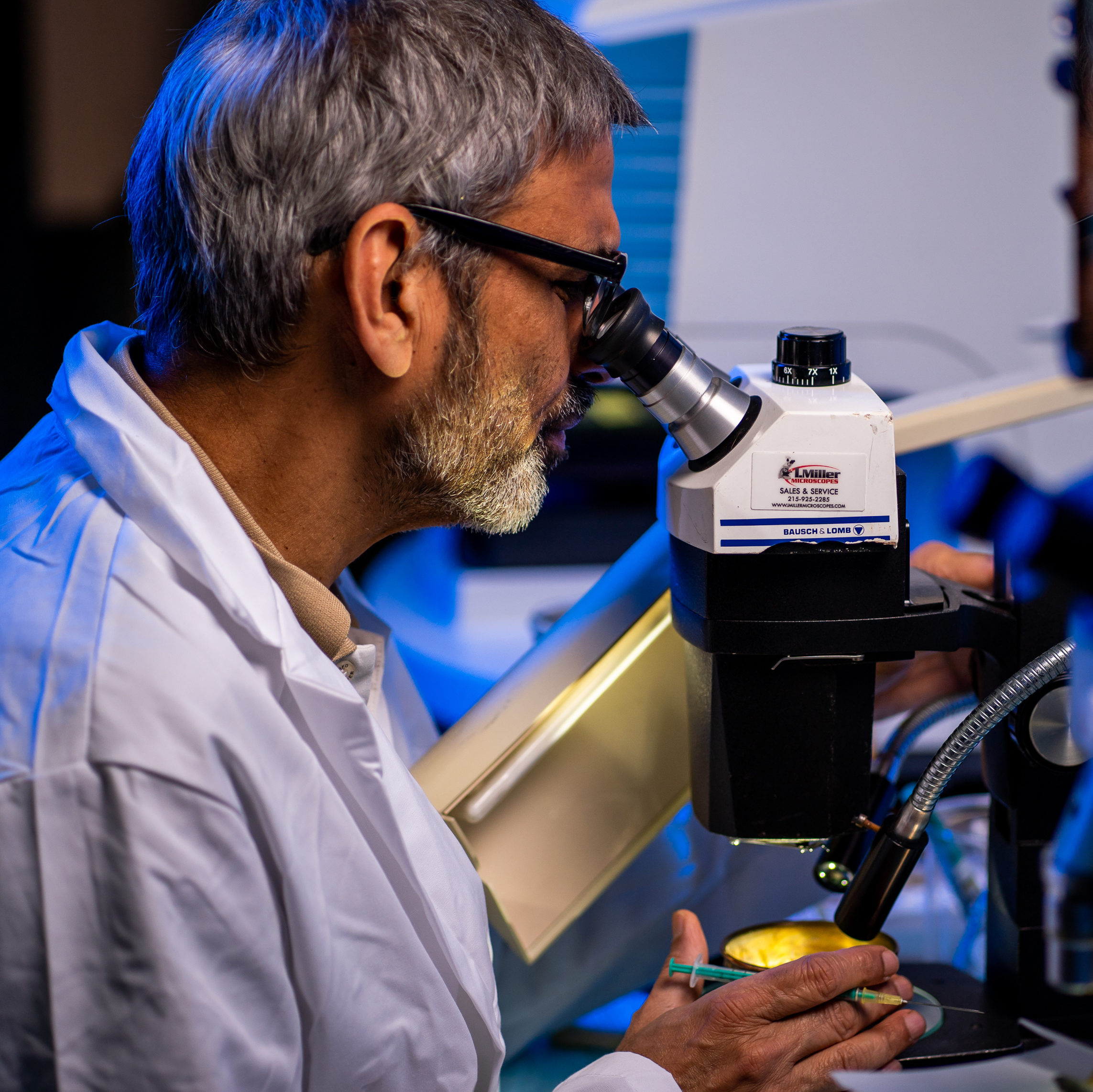

Cryptosporidium, a microscopic organism sometimes found in freshwater, can cause illness in humans. We are one of the nation’s leaders in Cryptosporidium research. We work closely with the Philadelphia Department of Public Health to ensure our tap water is free of Cryptosporidium and other organisms.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are potentially harmful chemicals that have been used in industry and many consumer products. We voluntarily test for PFAS in the city’s rivers and creeks. PWD’s water sampling has not detected amounts at or above the EPA’s health advisory levels.

A recent independent test by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection showed no detectable PFAS concentrations in Philadelphia’s treated drinking water.

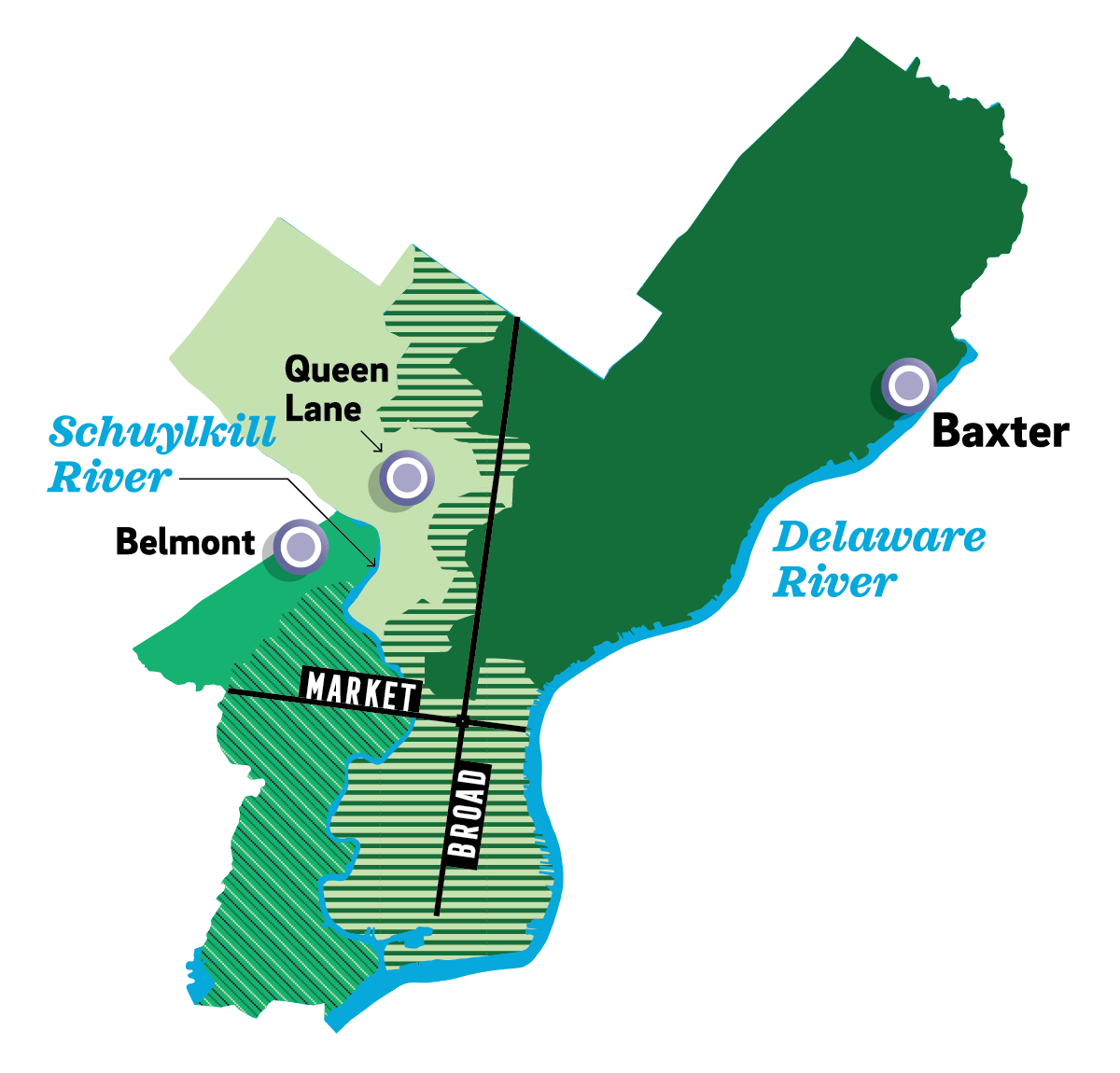

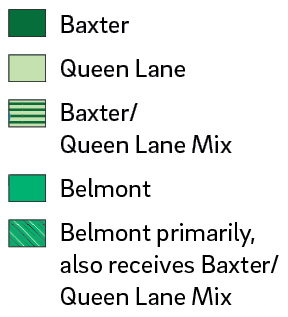

One city.

Two rivers.

Three treatment plants.

Philadelphia has two rivers that provide our drinking water: the Delaware River and the Schuylkill River. PWD operates three water treatment plants: Baxter, Queen Lane, and Belmont.

Where you live in Philadelphia determines which plant(s) treat your water!

Enter your address to find out where you get your water:

High-quality staff.

High-quality results.

The experts working at our treatment plants take pride in using water drawn from our local rivers.

Hundreds of millions of gallons of top-quality drinking water are produced every day.

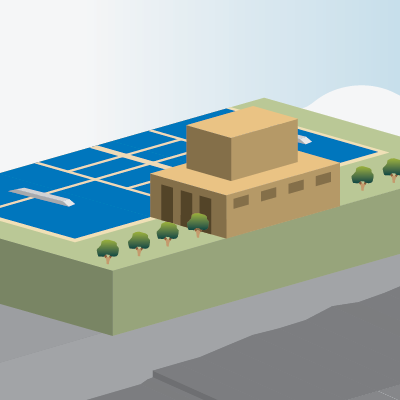

Drinking Water Treatment Plants:

An important early step in water’s journey.

Treatment processes

Once collected, river water goes through multiple processes to ensure it’s crystal clear and safe.

Gravity settling

River water is pumped to reservoirs. Sediment settles.

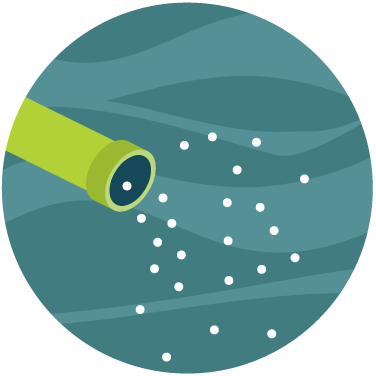

Disinfection

We add Sodium Hypochlorite to kill harmful organisms.

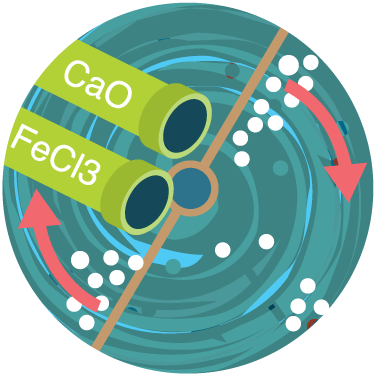

Coagulant, flocculation, and pH

Gentle mixing helps particles clump together. We also adjust the acidity.

Additional settling

Clumps of particles settle and are removed.

Additional disinfection

We add Sodium Hypochlorite a second time to kill any remaining harmful organisms.

Filtration

Filters remove more microscopic particles.

Additional treatment

Ingredients like Fluoride, Zinc Phosphate, and Ammonia help keep water healthy and safe.

Before it leaves the plant

We test our treated water for about 100 regulated contaminants, ranging from organisms like bacteria to chemicals like nitrate.

In 2020, we found no violations under state and federal regulations.

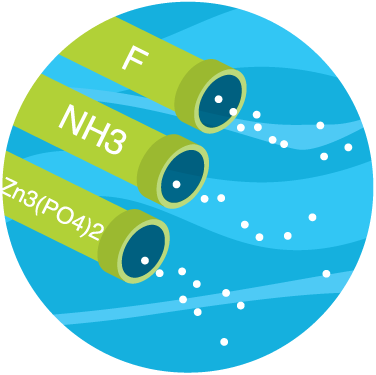

Final touches

Chlorine + Ammonia

Chlorine protects us from organisms found in untreated water that can cause disease. Ammonia is added to make the chlorine last longer and reduce the bleach-like smell.

Fluoride

All water contains some fluoride. We adjust the natural levels slightly to help protect your teeth against decay.

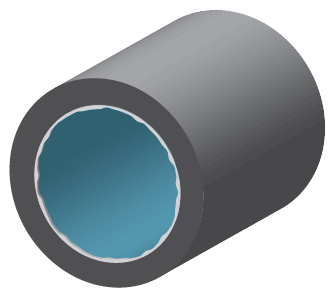

Zinc orthophosphate

Zinc orthophosphate is a compound that helps a protective coating form on pipes. It prevents corrosion (or breaking down over time).

A Closer Look

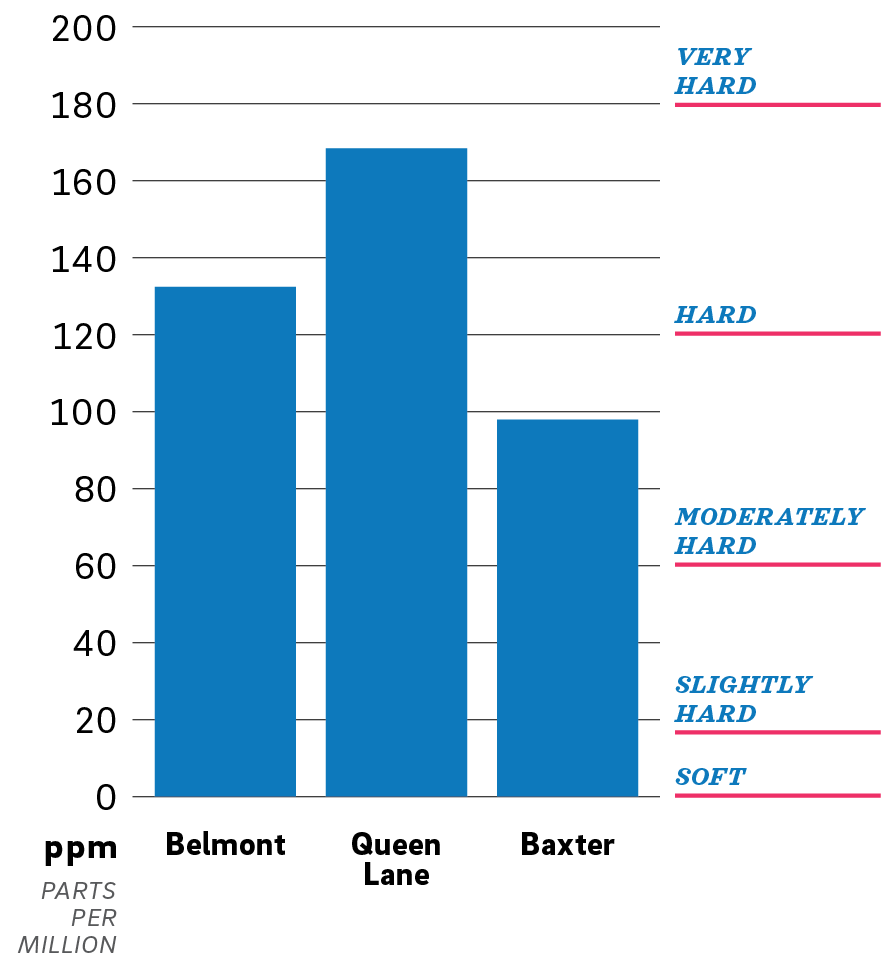

Hardness

The hardness of water is determined by the minerals naturally dissolved in it.

Hardness can vary based on natural conditions – for example, a drought can impact hardness.

Hardness matters if you use your water for activities like brewing beer or keeping a home aquarium. Customers often ask about hardness when researching appliances like dishwashers.

2020 Results

What this means for you

Hardness matters if you use your water for activities like brewing beer or keeping a home aquarium.

Most customers don’t need to monitor their water’s hardness.

☑ Result:

Philadelphia’s water is moderately hard or hard, depending on which treatment plant serves your neighborhood.

Part Two Delivery

Large scale water mains help transport water from treatment plants to customers.

A safe path through the system

We have about 3,100 miles of water mains that deliver clean tap to customers. To ensure water stays safe as it moves from the plant to you, we take samples and monitor real-time water quality data, 24/7.

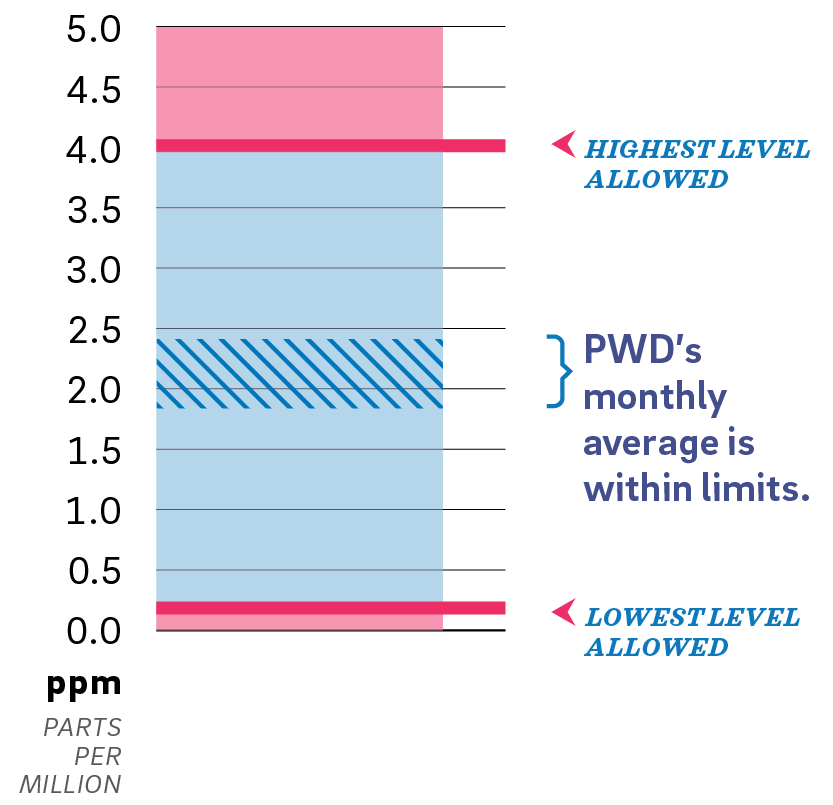

A Closer Look

Residual Chlorine

This test is done throughout the system. It checks that the chlorine added at plants remains at levels that keep water fresh and safe while staying within regulations.

2020 Results

What this means for you

We travel the city to collect samples of drinking water from fire and police stations, pumping stations and more.

We do over 420 of these tests every month!

☑ Result:

Better than standards.

Real-time results

We use sensors throughout the system to track water quality in real-time.

These extra tests let us know if the quality changes as the water travels through our network of mains.

25-year Drinking Water Plan

Over 400 significant improvements, including 10 key projects, are designed to strengthen the system that has served this city for centuries. From pumping stations to water mains, we’ll keep the water safe as it flows across the city. And we’re making sure our infrastructure is reliable, robust and resilient, for today and tomorrow.

Part Three: At Home

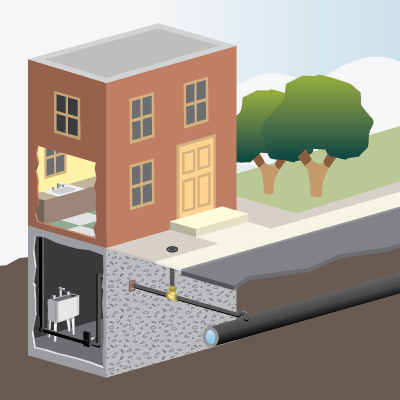

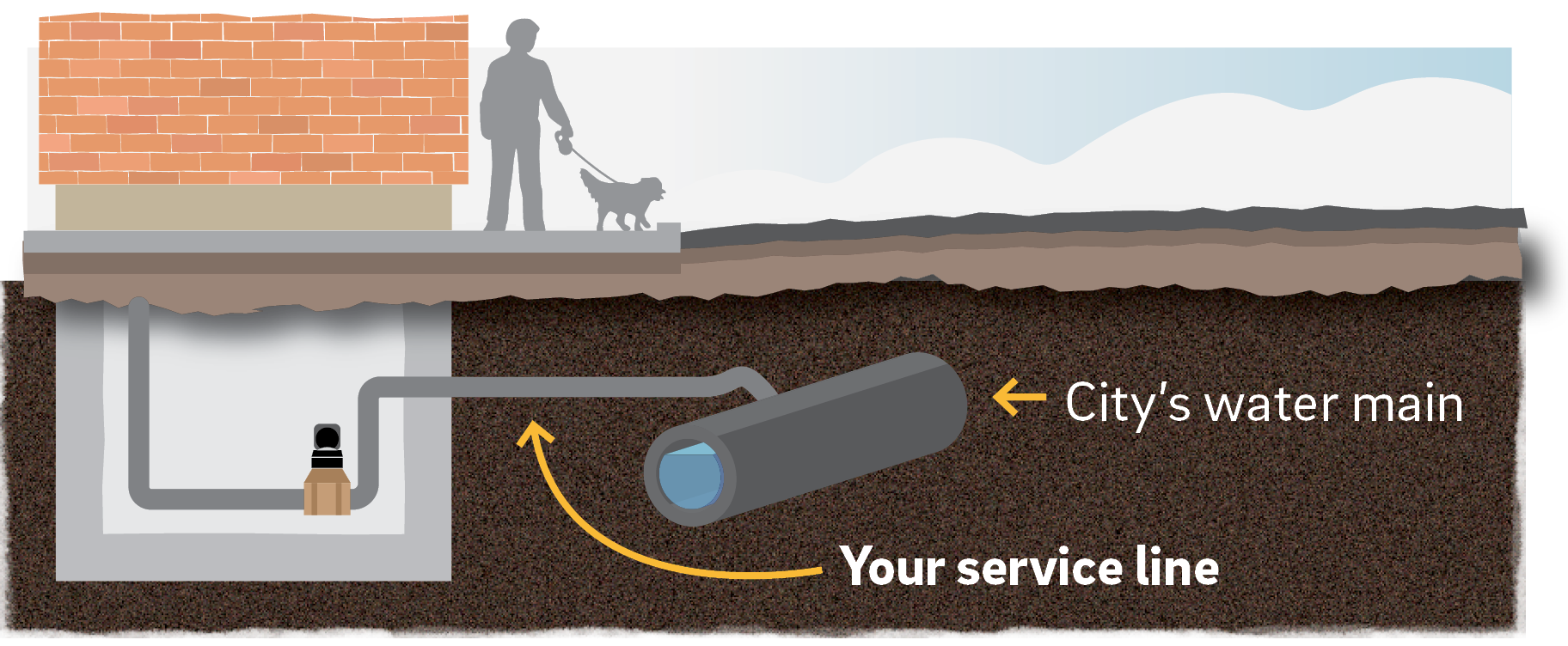

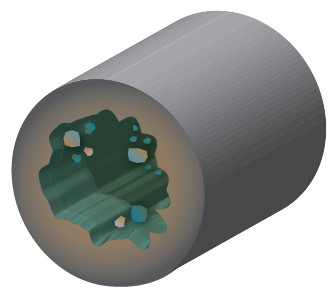

Every home on your block relies on a service line to carry water from the main to the property.

Your Service Line: The final stretch

Once it leaves our water main and enters your service line, you and your property’s plumbing can play a role in keeping water safe.

Most people don’t know this is part of their home’s plumbing.![]()

Corrosion Control

Philadelphia has a corrosion control program mandated by federal law and optimized over the past two decades. It minimizes the release of lead from service lines, indoor pipes, fixtures, and solder by creating a coating designed to keep lead from leaching into the water.

What do we mean by “flushing your pipes”?

Flushing pushes the water that is sitting in pipes out and down your drain until clean water comes through the tap. When pipes are disturbed during construction or repairs, they might require flushing.

Clean water starts at

our water mains.

Running the tap gets rid

of water sitting in pipes.

Healthy home habit

If you haven’t used water for 6 hours or more: Run your cold water for 3-5 minutes. This will flush out water that’s been sitting in your pipes.

It only costs a penny or two to ensure top-quality tap!

Talking about tap water

In neighborhoods across Philadelphia, our customers tell us what matters to them. When it comes to tap water, there’s a lot to talk about!

For starters, some residents are surprised they can get great drinking water right at home for less than a penny per gallon.

In each conversation, we hear loud and clear: Safe drinking water is a top priority, and lead is a topic people want to learn more about.

Our drinking water mains are not made of lead.

However, some older buildings may have lead plumbing.

Lead in a property’s plumbing

A home’s older fixtures & valves:

Lead can be found in older fixtures and valves, and in old solder, where pipes are joined.

Service Line:

This pipe connects a property’s plumbing to the water main in the street and is the responsibility of the property owner.

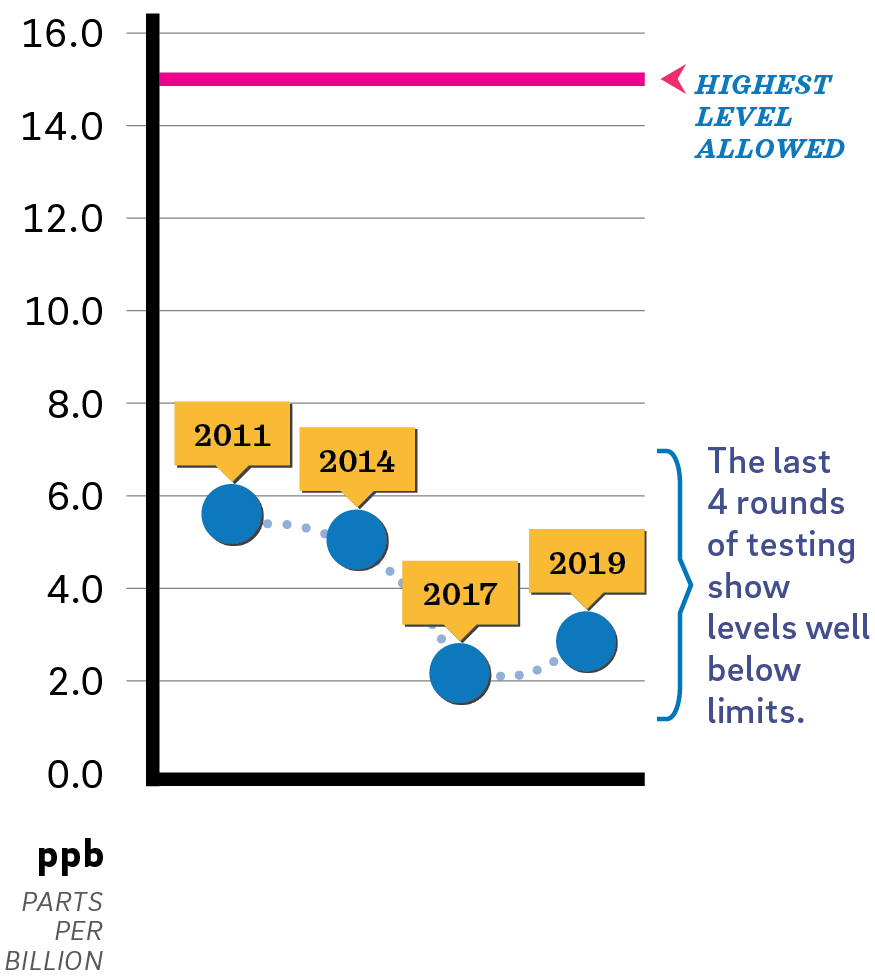

A Closer Look

Carefully monitoring Lead

In addition to regular tests in customer homes, every three years we complete a rigorous round of sampling for lead and copper. We take samples from homes that have lead service lines.

We share the results with the EPA and the public.

The EPA requires that 90% of homes show lead levels less than 15 ppb.

Recent results

What this means for you

Soon, the EPA will update their guidelines for sampling. This will impact future results. We support this effort to make sure the sampling is accurate, and to help identify homes with lead plumbing.

☑ Result:

Lead levels are consistently lower than limits set by the EPA.

US EPA Guidance

The EPA requires public water providers like the Philadelphia Water Department to monitor drinking water for lead at customer taps. If lead levels are higher than 15 parts per billion (ppb) in more than 10% of taps sampled, water providers must inform customers and take steps to reduce lead in water.

If present, elevated levels of lead can cause serious health problems, especially for pregnant women and young children. Lead in drinking water is primarily from material and components associated with service lines and home plumbing.

The Philadelphia Water Department is responsible for providing safe drinking water but cannot control the variety of materials used in plumbing components. If you haven’t turned on your tap for several hours, you can minimize the potential for lead exposure by flushing your tap before using water for drinking and cooking. If you are concerned about lead in your water, you may wish to have your water tested. Information on lead in drinking water, testing methods, and steps you can take to minimize exposure is available from the Safe Drinking Water Hotline (800) 426-4791 or at: www.epa.gov/safewater/lead.

We offer a zero-interest loan for replacing lead service lines.

The Homeowners Emergency Loand Program (HELP) can cover the cost of a replacement.

Learn more & apply: www.phila.gov/water/helploan

2020 Data tables & more

All of PWD’s results are better than the recommended federal levels designed to protect public health.

This data shows how our process keeps your drinking water safe.

By reporting these results in these tables, we are meeting a requirement of the EPA.

Some contaminants may pose a health risk at certain levels to people with special health concerns.

Others are used as indicators for treatment plant performance.

What’s a “PPM”?

Many of these results are reported as “parts per million (ppm)” or “parts per billion (ppb)”.

Here’s what that looks like:

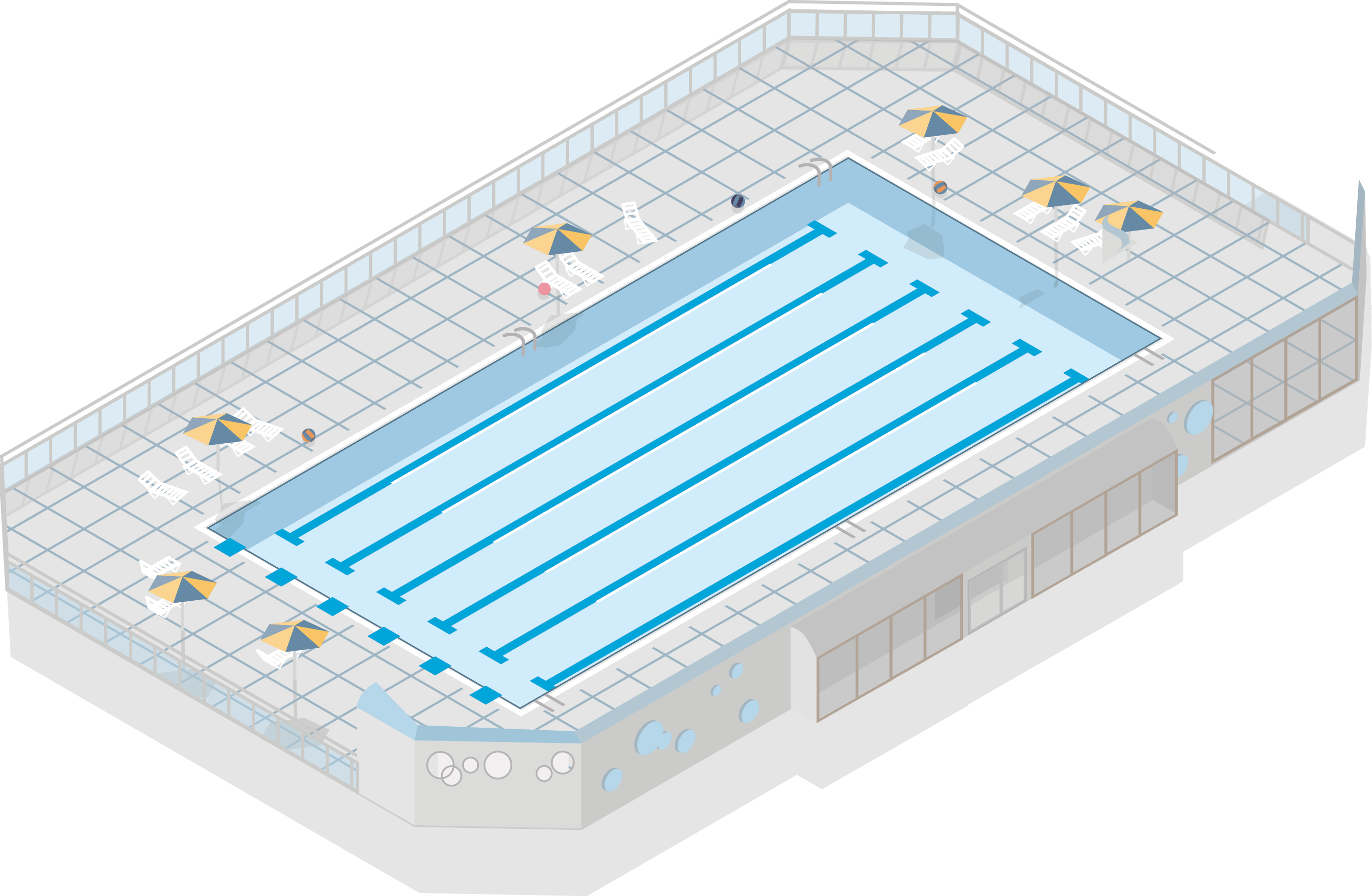

PPM vs. PPB

ppm (parts per million):

Denotes 1 part per 1,000,000 parts, which is equivalent to two thirds of a gallon in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

ppb (parts per billion):

Denotes 1 part per 1,000,000,000 parts, which is equivalent to half a teaspoon in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

For more abbreviations and their definitions, visit the Glossary.

Illustration: GoodStudio / Shutterstock.com, and Philadelphia Water Department

What we test for and how

Public drinking water systems monitor their treated drinking water for approximately 100 regulated contaminants. These regulatory parameters are defined within federal rules such as the Revised Total Coliform Rule, Surface Water Treatment Rule, Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rules, Lead and Copper Rule and the Radionuclides Rule.

We monitor for the regulated parameters listed below.

Any contaminants found are noted in the tables on the following pages:

Inorganic Chemicals

Antimony

Arsenic

Barium

Beryllium

Cadmium

Chromium

Copper

Cyanide

Fluoride

Lead

Mercury

Nickel

Nitrate

Nitrite

Selenium

Thallium

Synthetic Organic Chemicals

2,3,7,8 – TCDD (Dioxin)

2,4 – D, 2,4,5 – TP (Silvex)

Alachlor

Atrazine

Benzopyrene

Carbofuran

Chlordane

Dalapon

Di(ethylhexyl)adipate

Di(ethylhexyl)phthalate

Dibromochloropropane

Dinoseb

Diquat

Endothall

Endrin

Ethylene Dibromide

Glyphosate

Heptachlor

Heptachlor epoxide

Hexachlorobenzene

Hexachlorocyclopentadiene

Lindane

Methoxychlor

Oxamyl

PCBs Total

Pentachlorophenol

Picloram

Simazine

Toxaphene

Volatile Organic Chemicals

Benzene

Carbon Tetrachloride

1,2-Dichloroethane

o-Dichlorobenzene

p-Dichlorobenzene

1,1-Dichloroethylene

cis-1,2-Dichloroethylene

trans-1,2-Dichloroethylene

Dichloromethane

1,2-Dichloropropane

Ethylbenzene

Monochlorobenzene

Styrene

Tetrachloroethylene

Toluene

1,2,4-Trichlorobenzene

1,11-Trichloroethane

1,1,2-Trichloroethane

Trichloroethylene

o-Xylene

m,p-Xylenes

Vinyl Chloride

Other factors that can impact drinking water

Appealing to Your Senses

We work to ensure your water looks, tastes and smells the way it should.

To meet all water quality taste and odor guidelines, we test for the following: alkalinity, aluminum, chloride, color, hardness, iron, manganese, odor, pH, silver, sodium, sulfate, surfactants, total dissolved solids, turbidity and zinc.

Temperature and Cloudiness

The temperature of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers varied seasonally in 2020 from approximately 36°–84° Fahrenheit. PWD does not treat the water for temperature.

Cloudiness in tap water most commonly happens in the winter, when the cold water from the water main is warmed up quickly in household plumbing. Cold water and water under pressure can hold more air than warmer water and water open to the atmosphere.

When really cold winter water comes out of your tap, it’s simultaneously warming up and being relieved of the pressure it was under inside the water main and your plumbing. The milky white color is actually just tiny air bubbles. If you allow the glass to sit undisturbed for a few minutes, you will see it clear up gradually.

Regulated Radiological Contaminants & Asbestos

In 2020, PWD monitored for radiological contaminants: uranium, gross alpha and combined radium and also asbestos at the three water treatment plants.

All results were non-detect.

2020 Data tables

Lead & Copper – Tested at Customers’ Taps: Testing is done every 3 years. Most recent tests were done in 2019.

| EPA’s Action Level – for a representative sampling of customer homes | Ideal Goal (EPA’s MCLG) | 90% of PWD customers’ homes were less than | Number of homes considered to have elevated levels | Violation | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead | 90% of homes must test less than 15 ppb | 0 ppb | 3.0 ppb | 2 out of 99 | No | Corrosion of household plumbing; Erosion of natural deposits |

| Copper | 90% of homes must test less than 1.3 ppm | 1.3 ppm | .28 ppm | 0 out of 99 | No | Corrosion of household plumbing; Erosion of natural deposits; Leeching from wood preservatives |

Inorganic Chemicals (IOC) – PWD monitors for IOC more often than required by EPA.

| Chemical | Highest Level Allowed (EPA’s MCL) | Ideal Goal (EPA’s MCLG) | Highest Result | Range of Test Results for the Year | Violation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony | 6 ppb | 6 ppb | 0.3 ppb | 0–0.3 ppb | No | Discharge from petroleum refineries; fire retardants; ceramics; electronics; solder |

| Barium | 2 ppm | 2 ppm | 0.049 ppm | 0.026–0.049 ppm | No | Discharges of drilling wastes; Discharge from metal refineries; Erosion of natural deposits |

| Chromium | 100 ppb | 100 ppb | 2 ppb | 0–2 ppb | No | Discharge from steel and pulp mills; Erosion of natural deposits |

| Fluoride | 2 ppm* | 2 ppm* | 0.75 ppm | 0.66–0.75 ppm | No | Erosion of natural deposits; Water additive which promotes strong teeth; Discharge from fertilizer and aluminum factories |

| Nitrate | 10 ppm | 10 ppm | 3.74 ppm | 0.66–3.74 ppm | No | Runoff from fertilizer use; Leaching from septic tanks; Erosion of natural deposits |

Total Chlorine Residual – Continuously Monitored at Water Treatment Plants

| Sample Location | Minimum Disinfectant Residual Level Allowed | Lowest Level Detected | Yearly Range | Violation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baxter WTP | 0.2 ppm | 2.34 ppm | 2.34–3.47 ppm | No | Water additive used to control microbes |

| Belmont WTP | 1.63 ppm | 1.63–2.87 ppm | |||

| Queen Lane WTP | 2.01 ppm | 2.01–3.64 ppm |

Total Chlorine Residual – Tested throughout the Distribution System. Over 360 samples collected throughout the City every month.

| Sample Location | Maximum Disinfectant Residual Allowed | Highest Monthly Average | Monthly Average Range | Violation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distribution System | 4.0 ppm | 2.43 ppm | 1.87–2.43 ppm | No | Water additive used to control microbes |

Total Organic Carbon – Tested at Water Treatment Plants

| Treatment Technique Requirement | Baxter WTP One Year Average | Belmont WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | Violation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of Removal Required | 25–45% | 25–45% | 15–45% | n/a | Naturally present in the environment |

| Percent of Removal Achieved* | 34–75% | 0–77% | 25–76% | No | |

| Number of Quarters out of Compliance* | 0 | 0 | 0 |

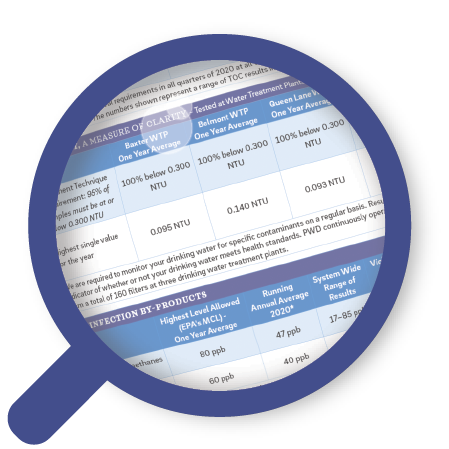

Turbidity, A Measure of Clarity – Tested at Water Treatment Plants

| Baxter WTP One Year Average | Baxter WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | Violation | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Technique Requirement: 95% of samples must be at or below 0.300 NTU | 100% below 0.300 NTU | 100% below 0.300 NTU | 100% below 0.300 NTU | n/a | Soil runoff, river sediment |

| Highest single value for the year | 0.095 NTU | 0.140 NTU | 0.093 NTU | No |

Disinfection By-Products

| Highest Level Allowed (EPA’s MCL) – One Year Average | Running Annual Average 2020* | System Wide Range of Results | Violation | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Trihalomethanes (TTHMs) | 80 ppb | 47 ppb | 17–85 ppb | No | By-product of drinking water disinfection |

| Total Haloacetic Acids (THAAs) | 60 ppb | 40 ppb | 10–65 ppb | No | By-product of drinking water disinfection |

Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring (UCMR)1

| Chemical | Testing Period | Average | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bromide2 | 1/14/2020 | 0.034 ppm | 0–0.052 ppm |

| Total Organic Carbon (TOC)2 | 1/14/2020 | 2.27 ppm | 2.19–2.34 ppm |

| HAA5 Total3 | 1/14/2020 | 21.3 ppb | 14.8–31.3 ppb |

| HAA6Br Total4 | 1/14/2020 | 7.1 ppb | 3.8–10.3 ppb |

| HAA9 Total5 | 1/14/2020 | 28.2 ppb | 23.6–35.5 ppb |

| Manganese | 1/15/2020 | 0.55 ppb | 0–0.95 ppb |

- 1 Unless otherwise noted, samples were collected from finished water sampling locations.

- 2 Bromide and TOC represent source water samples.

- 3 HAA5 Total – Dibromoacetic Acid, Dichloroacetic Acid, Monobromoacetic Acid, Monochloroacetic Acid, and Trichloroacetic Acid

- 4 HAA6Br Total – Bromochloroacetic Acid, Bromodichloroacetic Acid, Dibromoacetic Acid, Dibromochloroacetic Acid, Monobromoacetic Acid, and Tribromoacetic Acid

- 5 HAA9 Total – Bromochloroacetic Acid, Bromodichloroacetic Acid, Chlorodibromoacetic Acid, Dibromoacetic Acid, Dichloroacetic Acid, Monobromoacetic Acid, Monochloroacetic Acid, Tribromoacetic Acid, and Trichloroacetic Acid

In 2020, PWD performed special monitoring as part of the Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule (UCMR), a nationwide monitoring effort conducted by the EPA. Unregulated contaminants are those that do not yet have a drinking water standard set by the EPA. The purpose of monitoring for these contaminants is to help the EPA decide whether the contaminants should have a standard. For more information concerning UCMR, visit these websites: https://www.epa.gov/dwucmr/fourth-unregulated-contaminant-monitoring-rule or https://drinktap.org/Water-Info/Whats-in-My-Water/Unregulated-Contaminant-Monitoring-Rule-UCMR

Unregulated Contaminants Not Detected At Any of the Sampling Locations:

| 1‑Butanol, 2‑Methoxyethanol, 2‑Propen‑1‑ol, alpha‑Hexachlorocyclohexane, anatoxin‑a, Butylated Hydroxyanisole, Chlorpyrifos, Cylindrospermopsin, Dimethipin, Ethoprop, Germanium, Microcystin Total, Nodularin, o‑Toluidine, Oxyfluorfen, Permethrin Total, Profenofos, Quinoline, Tebuconazole, Tribufos |

Cryptosporidium – Tested at Source Water to Water Treatment Plants Prior to Treatment in 1/1/2017–3/31/2017

| Treatment Technique Required | Baxter WTP One Year Average | Baxter WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Number of Samples Collected | 6 | 6 | 6 | Naturally present in the environment. |

| Number of Cryptosporidium Detected | 15 | 2 | 6 | |

| 0.250 count/L | 0.033 count/L | 0.100 count/L |

Sodium, Hardness, and Alkalinity in tap water

The parameters listed below are not part of EPA’s requirements and are provided for information purposes.

WATER TIP :

Parameters like these matter if you use your water for activities like brewing beer or keeping a home aquarium.

Sodium in tap water

| Baxter WTP One Year Average | Belmont WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average (ppm) | 22 ppm | 39 ppm | 37 ppm |

| Average (mg in 8 oz. glass of water) | 5 mg | 9 mg | 9 mg |

| Range (ppm) | 16–32 ppm | 25–52 ppm | 26–44 ppm |

| Range (mg in 8 oz. glass of water) | 4–8 mg | 6–12 mg | 6–10 mg |

Hardness in tap water

| Baxter WTP One Year Average | Belmont WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 97 ppm or 6 gpg | 136 ppm or 8 gpg | 169 ppm or 10 gpg |

| Minimum | 81 ppm or 5 gpg | 100 ppm or 6 gpg | 127 ppm or 7 gpg |

| Maximum | 113 ppm or 7 gpg | 186 ppm or 11 gpg | 221 ppm or 13 gpg |

Alkalinity in tap water

| Baxter WTP One Year Average | Belmont WTP One Year Average | Queen Lane WTP One Year Average | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 38 ppm | 68 ppm | 75 ppm |

| Minimum | 25 ppm | 34 ppm | 49 ppm |

| Maximum | 53 ppm | 102 ppm | 111 ppm |

Glossary

Some of the words we use in the charts above may not be familiar to you. Here are definitions of technical and other terms.

- Action Level: The concentration of a contaminant which, if exceeded, triggers treatment or other requirements that a water system must follow. The action level is not based on one sample; instead, it is based on many samples.

- Alkalinity: A measure of the water’s ability to resist changes in the pH level and a good indicator of overall water quality. Although there is no health risk from alkalinity, we monitor it to check our treatment processes.

- E. coli (Escherichia coli): A type of coliform bacteria that is associated with human and animal fecal waste.

- gpg (grains per gallon): A unit of water hardness. One grain per gallon is equal to 17.1 parts per million.

- MCL (Maximum Contaminant Level): The highest level of a contaminant that is allowed in drinking water. MCLs are set as close to the MCLGs as feasible using the best available treatment technology.

- MCLG (Maximum Contaminant Level Goal): The level of a contaminant in drinking water below which there is no known or expected risk to health. MCLGs allow for a margin of safety.

- mg/L (Milligrams per liter): One milligram per liter is equal to one part per million.

- MRDL (Maximum Residual Disinfection Level): The highest level of disinfectant that is allowed in drinking water. The addition of a disinfectant is necessary for the control of microbial contaminants.

- MRDLG (Maximum Residual Disinfection Level Goal): The level of a disinfectant in drinking water below which there is no known or expected risk to health. MRDLGs do not reflect the benefits of the use of disinfectants to control microbial contaminants.

- Minimum Residual Disinfectant Level: The minimum level of residual disinfectant required at the entry point to the distribution system.

- NTU (nephelometric turbidity units): Turbidity is measured with an instrument called a nephelometer. Measurements are given in nephelometric turbidity units.

- Pathogens: Bacteria, virus, or other microorganisms that can cause disease.

- pCi/L (Picocuries per liter): A measure of radioactivity.

- ppm (parts per million): Denotes 1 part per 1,000,000 parts, which is equivalent to two thirds of a gallon in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

- ppb (parts per billion): Denotes 1 part per 1,000,000,000 parts, which is equivalent to half a teaspoon in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

- μg/L (Microgram per liter): One microgram per liter is equal to one part per billion.

- ppt (parts per trillion): Denotes 1 part per 1,000,000,000,000 parts, which is equivalent to one drop in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

- Service Line: The pipe that brings water from the water main into your home or business.

- SOC (Synthetic Organic Chemical): Commercially made organic compounds, such as pesticides and herbicides.

- Total Coliform: Coliforms are bacteria that are naturally present in the environment. Their presence in drinking water may indicate that other potentially harmful bacteria are also present.

- THAAs (Total Haloacetic Acids): A group of chemicals known as disinfection byproducts. These form when a disinfectant reacts with naturally occurring organic and inorganic matter in the water.

- TOC (Total Organic Carbon): A measure of the carbon content of organic matter. This measure is used to indicate the amount of organic material in the water that could potentially react with a disinfectant to form disinfection byproducts.

- TTHMs (Total Trihalomethanes): A group of chemicals known as disinfection byproducts. These form when a disinfectant reacts with naturally occurring organic and inorganic matter in the water.

- Treatment Technique: A required process intended to reduce the level of a contaminant in drinking water.

- Turbidity: A measure of the clarity of water related to its particle content. Turbidity serves as an indicator for the effectiveness of the water treatment process. Low turbidity measurements, such as ours, show the significant removal of particles that are much smaller than can be seen by the naked eye.

- VOC (Volatile Organic Chemicals): Organic chemicals that can be either man-made or naturally occurring. These include gases and volatile liquids.

- WTP: Water Treatment Plant

Top Customer Questions

How do I get my water tested?

We offer free lead and copper tests for residential customers who have concerns about their water.

To request an appointment Call (215) 685-6300

How hard is Philadelphia’s water?

Philadelphia’s water is considered moderately hard. Hardness depends on the treatment plant that serves your area of the city.

Why does water have an earthy flavor sometimes?

Earthy or musty flavors occur naturally in drinking water and are among the most commonly reported worldwide. When certain algae-type organisms grow in our rivers, detectable levels of these odors can make their way into the treated drinking water.

These natural compounds have no known health effects at their natural levels, and are found in various foods.

We take steps to reduce their presence when detected.

Why do water utilities add fluoride to water?

It’s a natural element that helps prevent cavities. Philadelphia’s Health Department (and dentists) recommend that we add fluoride to a level that helps protect children’s teeth.

Can I replace a lead service line?

Yes. If you don’t want to contact a plumber directly, apply for our Homeowners Emergency Loan Program (HELP).

A zero-interest loan can cover the cost of replacement.

Also: PWD will replace lead service lines for free if they are discovered during planned work on water mains.

Why does my tap water smell like a pool sometimes?

The smell of chlorine means your water is safe and treated to remove harmful organisms. You can reduce the smell by keeping a pitcher of fresh water in the refrigerator. This also reduces the earthy odor sometimes produced by algae in the rivers during spring.

Working together

Keep trash out of our waterways. Make sure to put your recyclable paper, metal, and plastics in a recycling bin, and disposable gloves, masks, food waste, and other garbage in a trash can, so they don’t end up in our rivers and streams.

Don’t flush anything but toilet paper – even “flushable” wipes. They don’t dissolve like toilet paper and can lead to clogs and backups, causing waste to flow into our homes and our streets.

Always properly recycle or dispose of household hazardous wastes. Don’t flush them down the toilet or down the sink, and don’t pour them into storm drains. Many storm drains flow directly to our streams and rivers.

Join a cleanup. ![]()

Group cleanups help remove trash and litter from our waterways. To learn about upcoming cleanups, keep an eye on the @PhillyH2O Blog and social media, email waterinfo@phila.gov, or call (215) 685-6300.

Sign up for email or text message updates from PWD to get the latest news, useful information, and find out about upcoming events. You can sign up for email and text alerts at phillyh2o.info/signup.

Take a tour. Tour a water treatment plant to learn more about how we test and treat our water, or visit Green Stormwater Infrastructure (GSI) sites to learn how Philadelphia is using GSI to keep our water cleaner and make our city greener. To schedule a tour, email waterinfo@phila.gov.

![]() Check out the Fairmount Water Works Interpretive Center for educational programming and resources on topics from our water infrastructure, watersheds, and local native wildlife to STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math).

Check out the Fairmount Water Works Interpretive Center for educational programming and resources on topics from our water infrastructure, watersheds, and local native wildlife to STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math).

Organizations we partner with

- American Water Resources Association

- American Water Works Association

- American Water Works Association Partnership for Safe Water

- American Public Works Association

- Association of Metropolitan Water Agencies

- National Association of Clean Water Agencies

- Partnership for the Delaware Estuary

- Schuylkill Action Network

- Schuylkill River Restoration Fund

- Tookany/Tacony-Frankford (TTF) Watershed Partnership

- U.S. Water Alliance

- Water Environment Federation

- Water Environment Research Foundation

- Water Research Foundation

Sharing this report

Please share this report with all people who drink this water, especially those who may not have received this notice directly (for example, people in apartments, nursing homes, schools and businesses). You can do this by posting this notice in a public place or distributing copies by hand and mail.

To receive a printed copy of this report, please email: waterquality@phila.gov

People with special health concerns

Some people may be more vulnerable to contaminants in drinking water than the general population. Immunocompromised persons, such as persons with cancer undergoing chemotherapy, persons who have undergone organ transplants, people with HIV/AIDS and other immune system disorders, and some elderly people and infants can be particularly at risk from infections. These people should seek advice about drinking water from their health care providers.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)/Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Guidelines on appropriate means to lessen the risk of infection by Cryptosporidium and other microbial contaminants are available from the Safe Drinking Water Hotline: (800) 426-4791.

Images

JPG Photo & Video

Sahar Coston-Hardy

Philadelphia Water Department