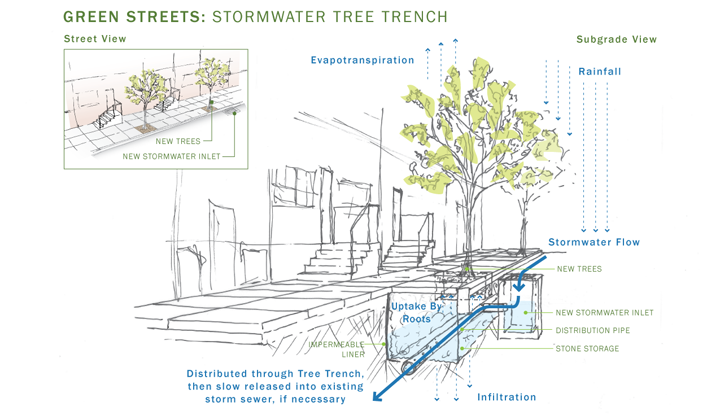

This diagram shows how trees move water from the soil to the air, creating what one NPR source describes as “massive, invisible flying rivers.” Image Credit: Philadelphia Water

This diagram shows how trees move water from the soil to the air, creating what one NPR source describes as “massive, invisible flying rivers.” Image Credit: Philadelphia Water

Evapotranspiration. A real mouthful, right? But it’s also a word we like to use when explaining how Green City, Clean Waters and green stormwater infrastructure helps the city manage billions of gallons of excess water we get from storms.

Essentially, we are talking about trees and plants moving water from the ground to the air, sucking it up through the roots, and breathing it out in the air.

Antonio Nobre, one of Brazil’s leading climate scientists, described the impact of evapotranspiration in a very cool way while talking to NPR’s Lourdes Garcia-Navarro in early November:

“What it creates, Nobre says, are these massive, invisible flying rivers.”

Flying rivers? Quite the image, eh?

Nobre was talking about how the Amazon rainforest may be creating its own climate, and a big part of his “flying rivers” idea has to do with the massive, planetary scale of the South American rainforest, which covers more than 2.7 million square miles.

At just 141 square miles and mostly not forest, Philly doesn’t have a fraction of the trees needed to create the effect Nobre refers to, so maybe instead of flying rivers, we can think of our urban tree network as a system capable of releasing flying springs of fresh water back into the air? Still pretty cool, right?

Here’s a little more about why that process is important for us in Philly:

Like a lot of cities with older water infrastructure, we have a combined sewer system in many neighborhoods that handles both sewage and water from storms. When there’s heavy rain, it can lead to overflowing sewers and a mixed mess of polluted stormwater and wastewater spilling into our rivers.

Green infrastructure helps address that problem in a number of ways, but the basic goal of all our green tools is to clean and filter water and keep too much of it from entering the sewers during and after storms. Tools like rain gardens and tree trenches slow down and filter stormwater, but they also allow plants to soak it up.

This is where evapotranspiration comes into play.

The first part of the word—“evapo”—refers to the evaporation that occurs when we use green infrastructure to slow down stormwater. Instead of rushing into the sewers and rivers, it’s held closer to the surface with materials like soil and stone. There, it has a chance to slowly evaporate back into the atmosphere.

Transpiration, the second part of the term, is a little more complex.

We’re used to thinking of plants and trees soaking water up through their roots, but lesser-known is the fact that this isn’t a one-way street: trees and plants also put water back into the atmosphere through their leaves.

And that’s the transpiration Nobre refers to when he talks about those invisible flying rivers.

Evapotranspiration is (you guessed it) the combined amount of water that enters the air from evaporation and transpiration, and it’s an important part of what green infrastructure does for us. Even if we can’t begin to compare Philly to a rain forest, Green City, Clean Waters alone has added nearly 2,000 new trees to the city since 2011.

We’ll need a lot more, but it’s a good start, and every tree helps!

For your listening pleasure, we’ve embedded Antonio Nobre’s interview with NPR below.

They get into transpiration around the 2:35 mark, but the whole story is a great listen if you have time*:

*Rather read the story? You can get a full transcript by clicking here, or you can click here to download the interview and listen later.