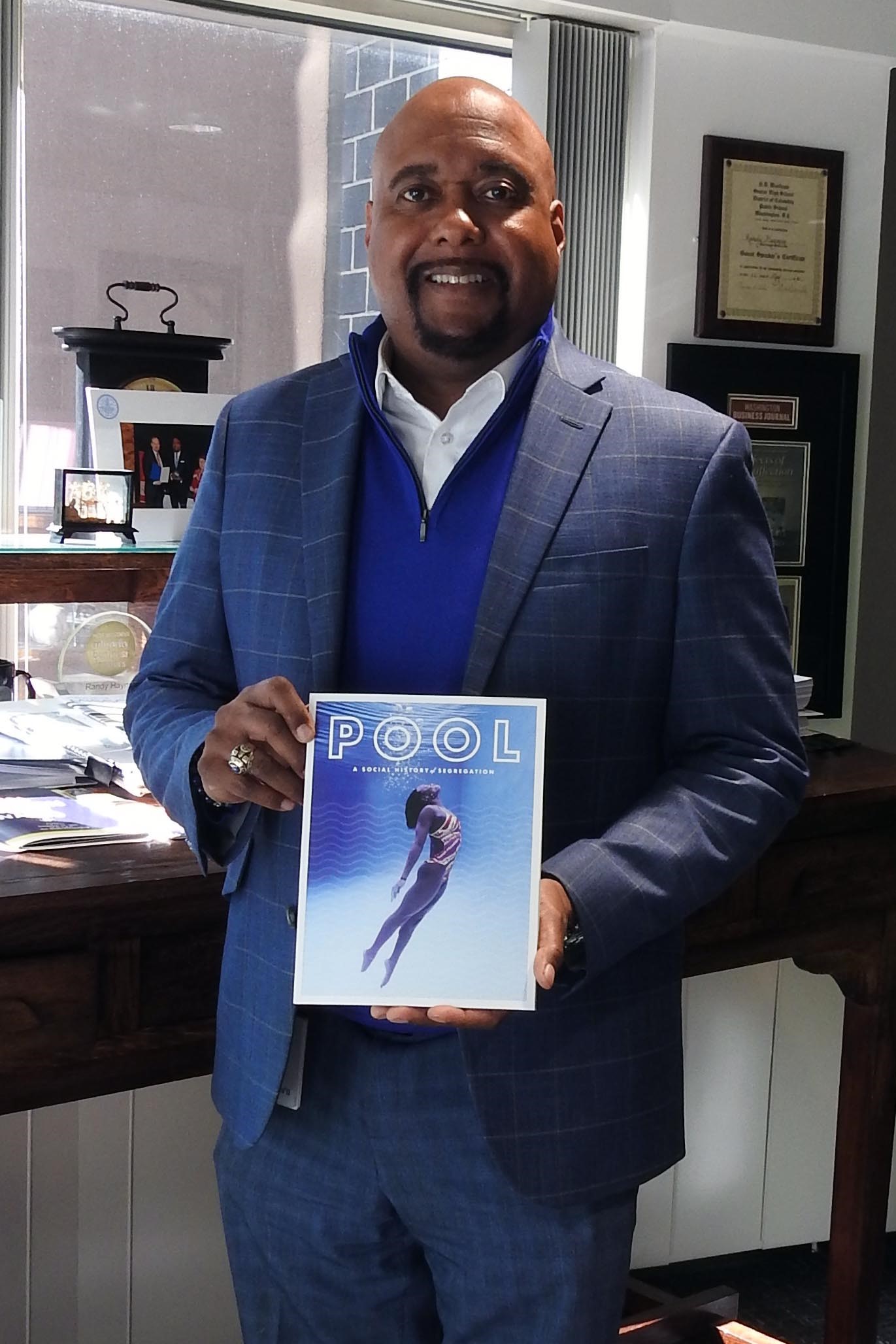

POOL: A Social History of Segregation, a multi-disciplinary museum exhibition that helps to illuminate a history of segregated swimming in America and its connection to present-day drowning issues affecting Black communities, will reopen to the public on March 22, 2023, due to popular demand! Learn more →

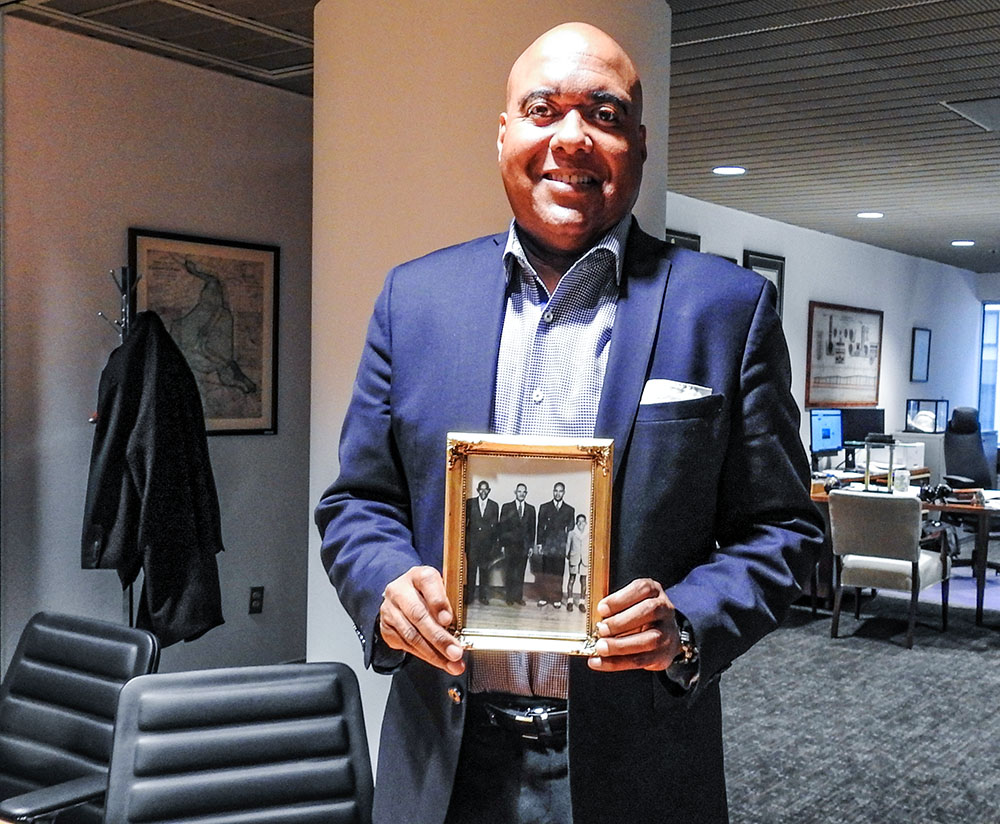

The following is an excerpt from the POOL Exhibit’s companion magazine, written by our own Philadelphia Water Commissioner, Randy E. Hayman, Esq.

Commissioner Hayman displays a printed copy of the POOL magazine.

Every 24 hours, the Philadelphia Water Department delivers about 230 million gallons of fresh, clear, life-sustaining water to the people who rely on us.

Despairingly, on average, roughly 11 people will succumb to drowning in America in that same period.

Within that troubling statistic is an even more devastating reality, which the POOL exhibit helps to uncover: America’s Black children are nearly six times more likely to drown than white children.

As the Water Commissioner here in Philadelphia, my day-to-day experience with water mostly comes down to ensuring we can continue to provide 1.6 million people with this precious resource, something that is essential for life.

Yet, when I step back to consider the disparities which can turn water from a source of life into a fatal threat, I see at the core of the problem a theme which ripples out into so many other areas of life where inequities cause harm: a lack of access.

At times throughout my life, I have heard remarks, made either jokingly or matter-of-factly, to the effect that “Black people cannot swim,” or that they are afraid of water. As the academics contributing to the POOL exhibit will note, there is some truth in that; Black Americans are half as likely to know how to swim as white Americans are, according to the CDC.

A more revealing way to put that, however, is that people who have never had access to pools and swimming lessons and the other experiences that make jumping in the water a thing of joy may rightly be afraid of water and never learn how to swim—no matter their skin color.

Growing up in North St. Louis, I had the great fortune of having a father who not only taught me to swim but who also put me on a path that opened many doors. My dad, a high school principal for 49 years, and my mother, also a long-serving educator, were an integral part of the educational community, and they helped my sisters and I attain the best schooling possible.

That meant we got to go to the John Burroughs School, which is to this day one of the best college-prep schools in the country. Named after a famous naturalist, the school would take kids out to a place called Camp Drey Land in the Ozarks every summer.

There, we would go out into the creek to swim and float around on rafts. It was a special experience. Being there as one of a few African Americans shortly after the school began desegregation efforts, I knew it was something not many of my friends at home would get to enjoy.

Of course, I was able to enjoy swimming at Drey Land because my father taught me to swim.

One of the earliest stories I remember pertaining to my father and swimming was his tale of getting into “Good Trouble,” as the late civil rights leader and Congressman John Lewis would have called it, at Kansas University, in Lawrence Kanas.

It was not easy being a Black college student in 1930 Kansas. In one anecdote, my father said they would give Black students an A in gym class, simply because they didn’t want any of the Black people sweating on other students during sports like wrestling.

In the face of that kind of treatment, they discovered a creative way to rebel. What they found out was that, if a Black person went into the pool, the school would incur the cost of emptying out the water and refilling it.

So as students, they would happen to fall in, just to make them refill this Olympic-size pool for swimming classes the next day. I loved that story. That was activism, at a personal level. Still, I also remember feeling a pang of fear for my father. How could he and his friends risk angering people, knowing what could happen?

Fairground Park Pool, where I learned to swim, is both a place of fond memories for me and a place that helped open my eyes to the history of racism which shaped St. Louis and the world around me.

Fairground was a good walk from my home. That was the sign that you were becoming a big boy, though not yet a teenager—when you could walk to the pool with a group of other kids, and you had to go through neighborhoods that weren’t yours.

The other part of becoming a big kid? You had to jump in the deep end and show that you could swim across the pool. That was the deep-water test.

Those are my warm recollections of Fairground.

Later, as a young adult, I saw pictures of the race riot that took place around Fairground Park and learned about the violence that took place, all because some white St. Louisans didn’t want African Americans to swim at the pool when it desegregated in 1949. (See Jeff Wiltse’s article in this magazine to learn more about the Fairground riot and similar events.)

Learning that there had been these riots at the Fairground pool made racism and segregation more palpable and real for me. It gave me a sense of the history of what people in St. Louis had been through.

With your eyes opened, you start to realize why neighborhoods are the way they are. People often try to put the blame on the individual or the community for the limitations they may have. But when you learn the history, and you see the way that people were treated and limited, how there wasn’t access, then you are not amazed that some people don’t know how to swim.

You can take that truth and apply it to many things in life.

A person might not have gone to law school, but were they smart enough to have done so? Absolutely.

A person may not have learned to swim, but did they have a pool? Did they have a coach beside them to show them the right way to dive?

No, but they certainly have the ability to swim. That ability was never tapped into. Why? Because they didn’t have access. We know that if you give Black people access to the right resources, we can win gold medals in the pool, like Simone Manuel.

You don’t need to be an Olympian to reap the rewards of swimming though. So much about learning swimming is about growth: overcoming something you’re afraid of. Jumping in. Learning new skills and tricks. Doing all of that until it becomes something fun that you love and you’re proud of.

And that growth only comes with exposure to places and people that can give you that opportunity.

Exposure to those experiences is what racism and segregation takes away from people. And it can leave scars that last for generations.

If you never have exposure to these things, and you only get to see yourself and those in your community in one light, you don’t develop appreciation for all of the parts of yourself and what you have the potential to do and become.

That’s why leveling access to pools, and swimming lessons, and beyond is so important. Our kids deserve to grow up unafraid of water and swimming and to actuate the strong potential that exists inherently inside them.

We know we have it in us: when you see young children playing together in the kiddie pool or at the beach, they do not care about race or what the other kids look like—they are just looking for someone to have fun with.

It’s not until the adult world interjects ideas of racism and differences that illusory limitations are fostered.

We can do better—and dialogues like the one started by the POOL exhibit are a crucial first step.

The POOL Exhibit is now open!

Our inspiring new exhibition explores the connection between water, social justice and public health.

Come see POOL: A Social History of Segregation at the Fairmount Water Works, open Wednesdays–Fridays from 12:00–5:00pm and Saturdays 10:00am–5:00pm, now through September!