Work to repair a cave-in caused by a sewer issue on Baltimore Avenue at 43rd Street is likely to be done by the end of June. We are in touch with residents and businesses working as quickly as possible with SEPTA to restore the #34 Trolley. Check the Alerts box on the SEPTA home page for updates.

The very large hole in the street uncovered something else: the city's deep interest in what's beneath our feet and the underlying history. PWD Historian Adam Levine is happy to help us satisfy that curiosity.

The following is a quick summary of the Mill Creek sewer story, told by the expert who maintains archives documenting our 200-plus years of history.

Mill Creek: ‘Stream to Sewer’ Backstory

Exactly 150 years ago, Philadelphia began a massive project that forever changed the city: transforming one of the area’s larger Schuylkill River tributaries into one of our largest sewers.

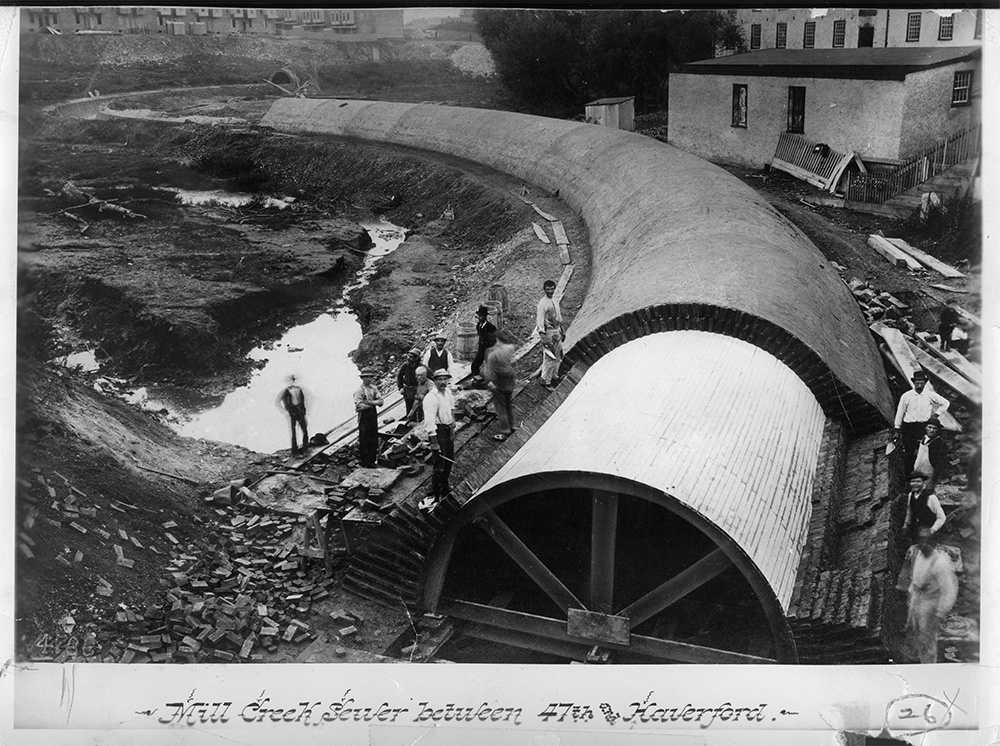

A historic photo shows Mill Creek Sewer under construction in 1887, looking upstream towards 47th Street and Fairmount Avenue.

Mill Creek and its numerous smaller feeder streams once drained about 7.2 square miles of West Philadelphia.

True to its name, the roughly six-mile waterway had about a dozen factories along its banks and also flowed through farmland. The headwaters bubbled up in Lower Merion Township, eventually meeting the Schuylkill River below Woodlands Cemetery. The suburban portion of the stream still sees the light of day.

In Philly, not so much: Beginning in 1869, the City of Philadelphia began burying Mill Creek in a giant sewer to provide drainage of stormwater and sewage for the quickly growing neighborhood. By the time the sewer was completed in the mid-1890s, all but a tiny tributary within the City limits had been piped underground.

By obliterating the stream—words used by the engineers of the day—and filling in a valley the waterway had spent millennia carving out, this creek-to-sewer project opened up thousands of new acres made available for development. Neighborhoods with tens of thousands of houses were subsequently built on the formerly rural land.

A Rare Look at Hidden History + Current Updates

PWD historian Adam Levine is teaming up with the University of the Sciences to host a free public event on Tues. June 25 at 6:15 p.m. at 600 S. 43rd St.

Join us as we dive deep into the history, provide updates about repairs, and highlight local Green City, Clean Waters projects. RSVP recommended, but not required:

Get Free Tickets

In the century-and-a-half since the sewer was built, fill covering the sewer system was washed away, in a number of areas, leaving behind land unable to sustain development. Some have since been reclaimed for recreation, community gardens, and urban farms. One of those spaces is Mill Creek Farm, which maintains local green stormwater tools as a Soak It Up Adoption partner.

Combined Sewers Go Out of Fashion

Before the sewer project, Mill Creek emptied stormwater and raw sewage directly into the Schuylkill with no treatment. A new sewer created in the 1950s intercepted the sewage and sent it to the Southwest Water Pollution Control Plant, about four miles south of where the original mouth of the sewer dumped into the Schuylkill, for treatment.

During wet weather, Mill Creek and other “combined sewers” can overflow, allowing diluted sewage and stormwater to spill into the Schuylkill untreated. That problem is the focus of our efforts to reduce the volume of stormwater going into sewers using green stormwater tools and other infrastructure through the Green City, Clean Waters program:

While Mill Creek was one of the more substantial tributaries Philadelphia buried, it was certainly not the first; that distinction goes to Dock Creek in Old City, which went under in the 1760s. We stopped turning streams into sewers in the 1940s, with parts of Sandy Run, a Pennypack Creek tributary, being the last project of its kind:

Cohocksink Creek, Gunner’s Run, and Wingohocking Creek are all former streams that today exist only on our sewer maps. The areas that drain into these historic waterways are sometimes referred to using a hybrid phrase that speaks to their past and present: sewersheds, as highlighted in this Pittsburgh map.

These projects were not without their problems. Collapses were common, especially in the 19th Century. Contractors taking shortcuts, combined with inadequate City inspection, resulted in shoddy work in many places. The Mill Creek Sewer collapsed numerous times up until the 1970s, by which time the most vulnerable sections had been rebuilt.

Here, you can see a back-to-back image of the repairs being made and work being done at the same place in 1912:

The most tragic instance occurred in 1961. That year, a sewer caved in along Funston Street, sucking in four houses that were built directly atop. Casualties included three people, among them a nine-year-old boy.

In the aftermath, 115 houses built above the sewer were condemned and torn down. The incident served as a harsh history lesson for those residents who bought homes without realizing why the area was called Mill Creek.

Want to learn more from Philly's sewer history expert and see powerful historic images and documents?

Adam Levine's Mill Creek presentation is the result of decades of research. You are invited to for an event that explores our rich collection of archives, including maps, engineering diagrams, photographs and more.

In addition to updates on the Baltimore Ave. repair work, PWD Outreach Specialist Dan Schupsky will have information about local Green City, Clean Waters projects designed to address issues caused by combined sewers (like the Mill Creek Sewer).

We hope to see you at the June 25 talk.