Schuylkill River boaters paddle the waters just below Flat Rock Dam. Issues with water quality in Rio de Janeiro, home of the 2016 Summer Olympics, have local water sport enthusiasts thinking about the value of clean water.

With all eyes on Brazil for the 2016 Summer Olympics, one big health concern right up there with the Zika virus is the water quality in rivers, bays and surf around Rio de Janeiro. While athletes no doubt would prefer to focus their attention on winning, the risk of getting violently ill from the very water they’ll compete in and on is a serious hurdle aquatic athletes will have to contend with this year.

Stories like this July 26 report from the New York Times offer an alarming glimpse of what happens when we fail to protect our waterways from pollution. Here’s what Olympians in sports like swimming and kayaking may (quite literally) get a taste of during the Rio games, according to the Times:

Recent tests by government and independent scientists revealed a veritable petri dish of pathogens in many of the city’s waters, from rotaviruses that can cause diarrhea and vomiting to drug-resistant “superbacteria” that can be fatal to people with weakened immune systems.

As disturbing as this reality is, especially for the residents of Rio, it also has Philadelphia’s water sports advocates looking at our rivers with a renewed sense of gratitude and a reinvigorated commitment to keeping our waters clean and safe.

Perspective, media visiting Philly. #DemConvention https://t.co/QxtPvlfBS2

— Billy Penn (@billy_penn) July 27, 2016

Thanks to robust source water protection efforts by organizations like Philadelphia Water and high-tech, real-time water quality monitoring technology, waterways like the Schuylkill River can be used for activities ranging from standup-paddleboard yoga (a real thing!) to world-class races and regattas that bring tens of thousands of tourists and competitors to the city annually.

Take for example the TriRock Philadelphia Triathlon, held in Philly on June 25-26.

One of the top-rated urban triathlons in America, the 2016 TriRock offered two courses for its more than 3,000 participants, and both races began with a plunge into the Schuylkill River just above Peter’s Island, a large wooded patch of rocks jutting out of the river above the Columbia Bridge.

(Note: dangerous conditions make casual swimming in Philly rivers illegal, but event organizers can get special permits and use strict safety protocols to protect participants during swims.)

Decades ago, the idea of thousands of people taking a prolonged swim down the Schuylkill might have seemed outlandish, but the federal Clean Water Act and community efforts to protect the river from its headwaters on down have resulted in the remarkable recovery that makes the TriRock possible.

To protect our rivers from the kind of pollution that’s causing alarm in Rio, Philadelphia Water operates a vast wastewater system that treats an average of 432 million gallons of sewage each day.

That system includes three Water Pollution Control Plants consistently recognized as industry leaders, 19 pumping stations, approximately 3,716 miles of sewers, and a centralized biosolids handling facility that turns what you flush down the toilet into a fertilizer good enough for Florida citrus farmers to use in their orange groves.

Upstream of Philadelphia, more than 150 similar treatment plants on the Schuylkill River do their part to protect the river, treating many more millions of gallons of sewage daily.

To appreciate the work done by our Water Pollution Control Plants, imagine what our rivers look like now, and then imagine what they would look like with 432 million gallons of sewage flowing into them every day.

Now, take that smelly scene and multiply it by four—Rio de Janeiro is a city of 6.2 million—and you have an idea of not only what the Olympic athletes will be dealing with, but what the people living there have to deal with permanently.

A cleaner environment means 3,000 #estuarypeople can swim in the #SchuylkillRiver. #TriRockPhilly https://t.co/ZjqbyKnbbH

— Delaware Estuary (@DelawareEstuary) June 27, 2016

Good, But Not Perfect

Two safety factors still at play on local rivers, however, are combined sewer overflows and stormwater runoff from hard surfaces.

Combined sewer overflows are events involving sewer pipes that get flooded during heavy rains, causing a mix of stormwater and diluted sewage to wash into local waterways.

Like about 860 other cities and towns around the country, Philadelphia and other municipalities along the Schuylkill struggle with this issue, and all of them are working to reduce or eliminate sewer overflows.

While recent improvements made possible by Philadelphia Water’s Green City, Clean Waters program have reduced this kind of pollution by about 1.5 billion gallons during a typical year of rain, stormwater runoff can still raise the risk of people getting sick from swimming immediately after sizeable rainstorms.

When it rains, stormwater carries bacteria and other pollutants from the land—think of pet waste from streets, spilled motor oil from parking lots, chemicals from building roofs, and fertilizers from upstream farms—and washes them into our waterways.

That’s where monitoring by Philadelphia Water’s RiverCast program comes into play.

By looking at things like recent rainfall levels and data collected from U.S. Geological Survey gauges that measure how much water is flowing through area waterways, the RiverCast model uses historical data to forecast likely levels of bacteria that can make people who go swimming or do other water sports ill.

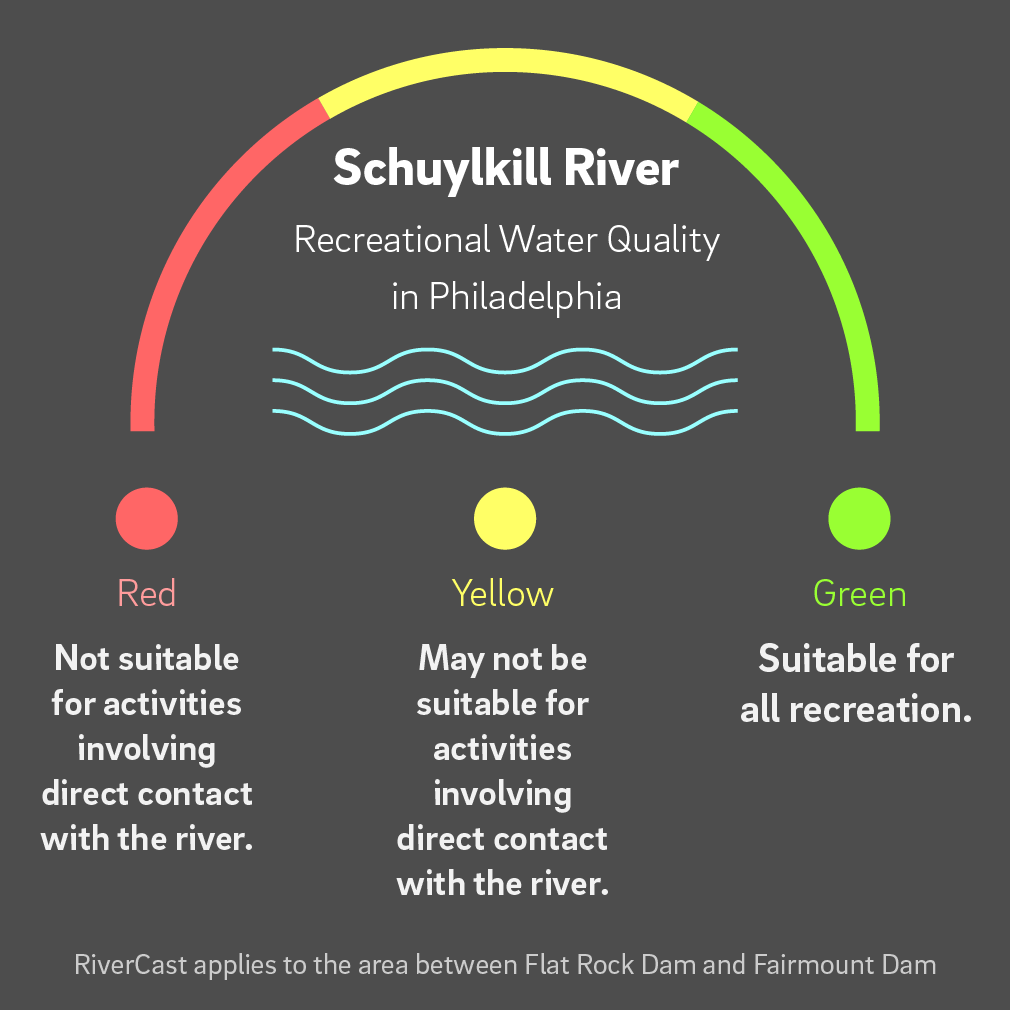

RiverCast provides information for the Schuylkill’s most popular recreation stretch within Philadelphia: from the Flat Rock Dam in Roxborough down to the Fairmount Dam at the Water Works. You can see the RiverCast coverage map here.

Using guidelines defined by the Environmental Protection Agency, who provided funding support for the program, RiverCast breaks the levels of risk down using a traffic-light style rating system:

Within the “red” rating, high water levels resulting in poor bottom visibility and increased drowning dangers are also considered because they can make even “secondary” recreation activities with little physical water contact—canoeing, rowing, power boating and fishing—risky.

To help event organizers and others make decisions about events that involve the Schuylkill River, hourly ratings are made public at www.PhillyRiverCast.org.

As a public health tool, RiverCast is designed to be conservative and minimize the likelihood that a rating will suggest the water quality is safer than it is likely to be. As a quality assurance measure, the Philadelphia Water team periodically compares past RiverCast ratings with corresponding bacteria data to validate the accuracy of the forecast.

Given the number of variables at play when trying to determine how safe a river like the Schuylkill is for recreation, the RiverCast forecasts are only a guideline and general estimate of water quality at a given period of time and should not be viewed as a direct measurement of water quality.

That said, the forecasts play an important role in the overall decision making process that comes into play whenever sporting and recreation events are held on the water. In the last month alone, RiverCast has been visited well over 13,000 times.

Leading up to the TriRock event, the page got thousands of visits, and the event organizers carefully watched the RiverCast rating while also taking their own water samples before making the call about whether to go forward with the 3,000+ Schuylkill plunges mentioned above.

Luckily for them, the days leading up to event were dry, and the risk of illness low.

An Olympic-Sized Problem

While a system like RiverCast can help Philly manage risks related to stormwater runoff, the infrastructure situation around Rio is grim enough to make using a similar monitoring technology there seem futile.

Philly’s problems are related to rain, but in Rio, many of the wastewater treatment plants don’t work properly or are completely off line—meaning raw sewage simply flows right into the water much of the time.

Water quality concerns in Rio have even inspired a textile engineer at Philadelphia University to create special suits with an antimicrobial finish designed to help protect athletes from contaminants:

Seamless, antimicrobial rowing suit makes its debut at the Olympics @Rio2016_en @Rio2016 https://t.co/svz4UT7ukO pic.twitter.com/HwKxCGQPny

— Tom Avril (@TomAvril1) June 24, 2016

For Philadelphia Water’s Beth Ventura, an environmental engineer who works diligently to protect local waterways from pollution and also took part in the 2016 TriRock race (she was in the river for 18 minutes and 28 seconds, if you’re wondering), the waterborne horror stories coming out of Rio drive home the importance of her work and the Clean Water Act.

She’s also glad the RiverCast system was there to help reassure her before her June swim with TriRock.

“Spending every day looking at water quality in the Schuylkill River, it’s not only the threats facing our waterways that are familiar to me,” says Ventura. “I also see all the dedicated people and organizations in Philadelphia and upstream communities working to protect and restore this beautiful river. Knowing the improvements that are underway and having RiverCast to give that extra confidence in the water quality that day, I knew it would be a great swim.”

And, while the issues with water quality here in Philadelphia and most U.S. waterways are hard to compare with the constant flow of untreated sewage in Rio, there is no guarantee that competing in America’s waterways won’t make you sick.

Just ask Maggie Hogan, a Philly native who’s competing in the Canoe Sprint for the U.S. Canoe-Kayak Team in Rio’s Summer Olympics.

We're lucky @PhillyH2O fights for #CleanWatersPHL: Lone U.S. Olympic kayaker to take water precautions https://t.co/vMdojOLdGB via @Reuters

— Brian Rademaekers (@Rad_PHL) August 2, 2016

“Unfortunately polluted water is a worldwide problem and the United States is no exception,” says Hogan. “The time I've been the most sick in my paddling career was a few years ago when a teammate and I contracted giardia from Mission Bay in San Diego. The global community needs to do more to protect our waterways.”

With so much attention on how dangerous water quality will likely have an impact on the 2016 Summer Games, it seems like more and more people will be waking up to that need, and the citizens of Philadelphia have a clear example in Rio that makes it graphically clear how important wastewater treatment and programs like Green City, Clean Waters and RiverCast are for public health and safety.

Like this story? You might also be interested in CSOCast, a page at Phillywatersheds.org that tracks combined sewer overflows on Philadelphia waterways. Check it out here.