During Black History Month, the Philadelphia Water Department and Fairmount Water Works are highlighting voices from “POOL: A Social History of Segregation,” a ground-breaking exhibit exploring how race and racism intersect with the world of swimming and water.

The day before POOL was supposed to officially open, the exhibit and much of the Water Works facility were submerged by the historic, devastating flood waters witnessed along the Schuylkill River following Hurricane Ida in September.

Thanks to the perseverance of the Water Works staff and the exhibit’s creator, Victoria Prizzia, POOL is currently set to return for a physical experience on World Water Day, March 22.

As we await the opening, we invite you to check out some excerpts from the exhibit’s companion magazine. To get things flowing, here is a sample of ‘Surfing in the African Diaspora,’ in which Dr. Kevin Dawson cuts against the standard origin story of surfing to highlight fascinating roots along Africa’s Atlantic coast.

Surfing in Africa and the Diaspora

By Dr. Kevin Dawson, courtesy of POOL

Popular histories of surfing tell us that Polynesians were the only people to develop surfing, that the first account of surfing was written in Hawai‘i in 1778, and that California surfers Bruce Brown, Robert August, and Mike Hynson introduced surfing to West Africa when they traveled there to film the 1966 movie “The Endless Summer.”

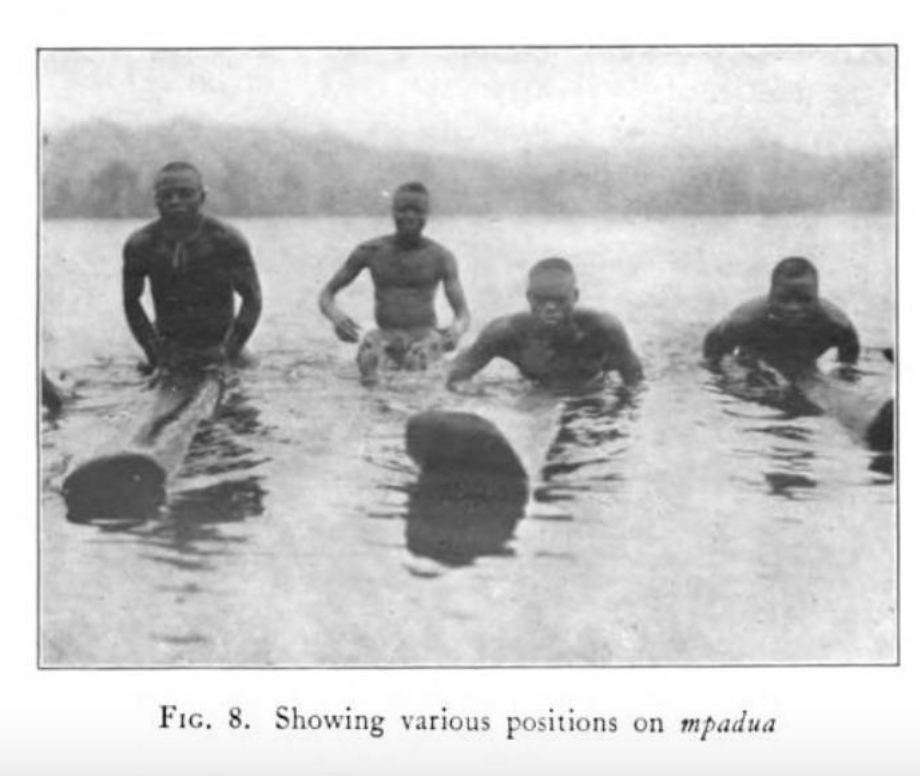

“Showing various positions on mpadua” illustrates the type of paddleboards used for centuries by the Asante on Lake Bosumtwi, in what is now Ghana. (1923)

Image/caption: “Surfing in Africa” and the Diaspora By Dr. Kevin Dawson, courtesy of POOL

All these claims are incorrect.

The modern surf cultures currently developing along Africa’s long shoreline are not something new and introduced; they are a rebirth, the remembering and re-imagining of 1,000-year-old traditions. The first known account of surfing was written during the 1640s in what is now Ghana. Surfing was independently developed from Senegal to Angola. Africa possesses thousands of miles of warm, surf-filled waters and populations of strong swimmers and sea-going fishermen and merchants who knew surf patterns and crewed surf-canoes capable of catching and riding waves upwards of ten feet high.

Africans surfed on three- to five-foot-long wooden surfboards in a prone, sitting, kneeling, or standing position, and in small one-person canoes. Despite Brown’s claim that “The Endless Summer” introduced surfing into Ghana, if viewers shift their eyes away from August and Hynson, they will see Ga youth of Labadi Village, near Accra, Ghana, riding traditional surfboards, which can still be found at some beaches, though most people now ride modern surfboards. The ability of Gamen, in the film, to stand on the Americans’ longboards illustrates their surfing tradition.

Africans also rode longboards, about twelve feet long, and used them to paddle several miles. English anthropologist Robert Rattray provided the best description and photographs of paddleboards on Lake Bosumtwi, located about 100 miles inland of Cape Coast, Ghana. The Asante believe the “anthropomorphic lake god,” Twi, prohibited canoes on the lake. Keeping with divine sanctions, people fished from paddleboards, called padua or mpadua (plural), and used them to traverse this five-mile (8.5 km) wide crater lake. While it is unclear if coastal peoples surfed these longboards, accounts and photographs illustrate that they paddled them a couple miles out to sea to anchored Western ships.

Two men on surfboards/paddleboards are seen in the top right corner of this early nineteenth-century postcard of Cotonou, in what is now the modern country of Benin. Throughout Africa, it was common for ship passengers to throw coins into the water and watch males dive underwater to retrieve them. The photograph perhaps predates the 1908 completion of Cotonou’s harbor

Image/caption: “Surfing in Africa” and the Diaspora By Dr. Kevin Dawson, courtesy of POOL

German merchant-adventurer Michael Hemmersam provided the first known record of surfing, which is problematic as he described a sport that was new to him.

Believing he was watching Gold Coast children, who were probably Fante in the Cape Coast, Ghana area, learn to swim, he wrote that parents “tie their children to boards and throw them into the water,” with other Europeans providing similar descriptions. Most Africans learned to swim when they were about sixteen months and with more positive reinforcement; such “lessons” would have resulted in many drowned children.

Later accounts are unambiguous. Describing the Fante of the Cape Coast and Elmina region in what is now Ghana, riding wooden surfboards, John Adam wrote in 1823, “[They] paddle outside of the surf, when, watching a proper opportunity, they place their frail barks on the tops of high waves, which, in their progress to the shore, carry them along with great velocity, . . . steering the planks with such precision, as to prevent them broaching to; for when that occurs, they are washed off, and have to swim to regain them.” Children “of not more than six or seven years of age, amuse themselves in this way, and swim like ducks.”

Likewise, in 1834, while at Accra, Ghana, James Alexander wrote: “From the beach, meanwhile, might be seen boys swimming into the sea, with light boards under their stomachs. They waited for a surf; and came rolling like a cloud on top of it.”

There are also accounts of Africans bodysurfing. In 1887, an English traveler watched an African man named Sua, at home “in his element, dancing up and down and doing fancy performances with the rollers, as if he had lived since his infancy as much in the water as on dry land.” As a wave approached, “he turns his face to the shore and rising on to the top of it he strikes out vigorously with it towards land, and is carried dashing in at a tremendous speed after the same manner as the [surf-canoes] beach themselves.”

Fishermen often surfed their six-foot-long paddleboards and surf-canoes weighing about fifteen pounds, with accounts describing both off the Cape Verde Islands, Ivory Coast, Congo-Angola, and Cameroon, with “Kru” canoes of Liberia being heavily documented. In 1861, Thomas Hutchinson observed Batanga fishermen from southern Cameroon riding surf-canoes “no more than six feet in length, fourteen to sixteen inches in width, and from four to six inches in depth” that weighed about fifteen pounds. Describing how work turned to play Hutchinson penned:

During my few days stay at Batanga, I observed that from the more serious and industrial occupation of fishing they would turn to racing on the tops of the surging billows which broke on the sea shore; at one spot more particularly, which, owing to the presence of an extensive reef, seemed to be the very place for a continuous swell of several hundred yards in length. Four or six of them go out steadily, dodging the rollers as they come on, and mounting atop of them with the nimbleness and security of ducks. Reaching the outermost roller, they turn the canoes stems shoreward with a single stroke of the paddle, and mounted on the top of the wave, they are borne towards the shore, steering with the paddle alone. By a peculiar action of this, which tends to elevate the stern of the canoe so that it will receive the full impulsive force of the advancing billow, on they come, carried along with all its impetuous rapidity.

The roughly six-foot-long dugout canoes that Batanga men surfed were smaller and lighter than contemporary surfboards.

Image: Mary H. Kingsley, West African Studies (London: 1901). Author’s collection (courtesy of POOL / Dr. Kevin Dawson)

Surfing was a means for opening up economic opportunities.

Surfing was a means for opening up economic opportunities. It allowed African youth to critically understand surf-zones so they could uniquely traverse them in surf-canoes, linking coastal communities to offshore fisheries and coastal shipping lanes. Atlantic Africa possesses few natural harbors and waves break along much of its coastline. The only way many coastal people could access the ocean’s resources was by designing surf-canoes that sliced through waves when launching from beaches and were fast, agile, and maneuverable, allowing them to surf waves ashore.

Surfing was the intergenerational transmission of wisdom that transformed surf-zones into social and cultural places, where youth holistically experienced the ocean. Suspending their bodies in the drink and positioning themselves in the curl, they learned about surf-zones by seeing and feeling how the ocean pushed and pulled their bodies. Youth learned about wavelengths (the distance between waves), the physics of breakers, and that waves form in sets with several minute intervals between sets. Importantly, surfing taught youth that to catch waves one needed to match their speed; something Westerners did not comprehend until the late nineteenth century. Documenting how surf-canoemen utilized childhood lessons, an Englishman noted that they “count the Seas [waves], and know when to paddle safely on or off,” often waiting to surf the last and largest set wave. In an age with few energy sources—when societies harnessed wind, animal, and, perhaps, river power—Atlantic Africans used waves to slingshot surf-canoes laden with fish or tons of cargo ashore, being the only people to bridle waves’ energy as part of their daily productive labor. Surf-canoemen floated colonial economies, transporting virtually all the goods exported out of and imported into Africa between ship and shore from the 1400s into the 1950s, when modern ports were constructed.

…

Kevin Dawson, Undercurrents of Power: Aquatic Culture in the African Diaspora (University of Pennsylvania Press: 2018) and “Surfing Beyond Racial and Colonial Imperatives in Early Modern Atlantic Africa and Oceania” in Alexander Sotelo Eastman and Dexter Zavalza Hough-Snee, eds., The Critical Surf Studies Reader (Duke University Press: 2017), 135-152.

Save the Date!

On Wednesday, March 2 at 12 p.m., The Water Center will host “The Water We Swim In: A Discussion on Water and Equity” virtual event. The panel, which includes PWD Community Outreach Specalist and We Can Swim! Co-founder Dan Schupsky,, will explore how pools can help lessen the impacts of climate change on communities of color and address issues of equity and inclusion.